September 2024

Volume 5

Part 7 - Replacement of the gas riser

Part 8 - The London Fire Brigade

HC 19–V

Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 26 of the Inquiries Act 2005

Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 4 September 2024

This report contains content which some may find distressing.

© Crown copyright 2024

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3.

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents.

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected].

ISBN 978-1-5286-5080-9

(Volume 5 of 7)

E03165832 09/2024

In his Phase 1 report the Chairman found that the supply of gas to the tower did not play a significant part in the outbreak or development of the fire on 14 June 2017 and that the employees of Cadent Gas Limited who attended to shut off the gas supply made appropriate decisions and executed their task admirably.[1] In this phase of the Inquiry we have investigated the replacement of one of the gas risers between 2016 and 2017. The works had not been finished at the time the fire occurred and we therefore thought it appropriate to consider whether they might have contributed to the spread of smoke or fire within the tower.

On completion of the refurbishment work to the tower in 2016 gas was supplied to residents by two pipelines which entered the basement below ground level on the east side: a ten-inch steel pipe that fed the boilers supplying hot water to residents[2] and a four-inch steel pipe that supplied gas to the flats.[3]

The pipe providing gas to the flats entered the basement at a high level. Four pipes, known as “risers”, ran vertically up into the tower; two of them were then split into two, making six risers in total.[4] These passed through the fabric of the building and directly into a cupboard in each flat. One of the risers supplied gas to all the “Flat 2s”.

The gas supply had been installed at the time the tower was built and by the time of the fire the pipework was almost 50 years old. It did not comply in a number of respects with current regulations.

On 1 October 2016, corrosion of the riser serving the “Flat 2s” made it necessary to cut off the supply of gas to all the “Flat 2s”.

Cadent Gas Limited (“Cadent”) is a gas transporter which owns and operates the pipes and apparatus that transport gas. Cadent does not own the gas itself but is paid by suppliers to deliver it through a network of pipes in a particular area. In the case of Grenfell Tower the area was that served by Cadent’s North London gas distribution network.[5] Cadent was responsible for the safety of the service pipework up to the point of the emergency control valve located at each customer meter; the installation pipework beyond the meter was the responsibility of RBKC as the owner of the building.[6]

The Health and Safety Executive monitors and oversees the health and safety of onshore gas distribution and supply[7] and Ofgem determines the funding and ensures the competitiveness of gas pricing.[8] Since the 1990s, in common with all gas transporters, Cadent is under certain statutory obligations, including obligations to:

Part of Cadent’s strategy to maintain service pipework for buildings in multiple occupation was to conduct a rolling programme of surveys.[12] On 30 September 2016 Cadent carried out a survey on Grenfell Tower[13] and identified three significant problems:

In response to the discovery of the leak Cadent immediately cut and capped the riser which supplied “Flat 2s”. That was completed in the early hours of 1 October 2016.[17]

Cadent used this and other information from the survey to calculate a building priority score[18] which indicated how often a building should be surveyed. The score for Grenfell was such that Grenfell Tower was placed on the list for discussion at the regular Cadent hazard and operability meetings, known as “HAZOP” meetings. The inability to find the missing pipeline isolation valves and the severe corrosion was noted on a schedule presented at the HAZOP meetings of 5 December 2016 and 23 February 2017.[19]

Pipeline isolation valves, by which the supply of gas to a building can be shut off quickly, are the main emergency control mechanism for buildings in multiple occupation.[20] They are mandatory on service pipelines to such buildings[21] and are located outside the premises so that access to them can be obtained easily through valve chambers with marked covers visible at pavement level. For obvious safety reasons, as part of making appropriate arrangements for responding to incidents and emergencies, gas transporters have a duty to maintain access to pipeline isolation valves.[22] Notwithstanding that, we were told that it was well known in the gas industry that pipeline isolation valves are often lost, for example, as a result of being covered over by landscaping or road works.[23] The survey of Grenfell Tower carried out by Cadent in 2008 showed that “fire valves” (another term for pipeline isolation valves) had been installed on the pipes supplying gas to the tower.[24] The fact that Cadent could not find them in 2016 was almost certainly attributable to the landscaping works completed as part of the refurbishment.[25]

Having discovered in October 2016 that the pipeline isolation valves could not be found, Cadent should have taken steps to reinstate them immediately but it appears that the appropriate team in Cadent was not notified about the need for that to be done. Mr Harrison, one of Cadent’s network directors, accepted that that had been a failure on its part which should not have occurred.[26]

The failure to reinstate the pipeline isolation valves did not affect the course of events surrounding the fire because burning debris falling on the east side of the tower would have prevented anyone from obtaining access to them.[27] However, on another occasion access to them might be of critical importance and we therefore think that all gas transporters should have a legal duty to inspect these emergency valves at intervals to ensure that they are accessible and to reinstate them if they are not.

Although steel pipes are very strong and have a long service life under normal conditions, they are susceptible to corrosion, particularly if exposed to damp. Because corrosion causes the steel to deteriorate and lose its integrity, keeping it within acceptable levels is an important part of maintaining the safety of pipelines.

Cadent commissioned a corrosion survey for Grenfell Tower on 5 December 2016.[28] Mr Harrison explained that the survey was not completed because of problems over obtaining access to the tower. A Cadent engineer attended on two occasions but could not get into the relevant parts of the building.[29] Although a decision was made in February 2017 to try again, the full corrosion survey had not been completed by the time of the fire, some eight months after the corrosion had been discovered.[30] As Mr Harrison accepted, that was unacceptable.[31]

After the fire it was found that a riser in Flat 115 had ruptured. It is possible that that was a result of a failure to keep corrosion levels within acceptable limits and occurred during the fire or later as the building continued to deform from its effects,[32] but we do not think it is necessary for us to reach a decision on that question and in any event do not have sufficient evidence to do so with any confidence. All we can say is that several factors may have contributed to the rupture of that particular pipe, one of which may have been corrosion that weakened it at one of its threaded joints.[33]

By June 2017 Cadent’s map of the gas pipes running into the tower should have shown all three systems: the pipe supplying the boilers, the original pipe supplying gas to the flats and the new pipe supplying gas to the “Flat 2s”. However, the maps available to the Cadent engineers who attended the fire only showed the pipe supplying the boiler.[34] Cadent should have known that its maps were inaccurate because those available when it carried out the survey in September 2016 also showed only the pipe supplying the boilers.[35]

Cadent maintained that its failure to correct the maps did not, in fact, have any material effect on the ability of its engineers to identify and isolate the gas supply pipes on the night of the fire, since they were able to obtain the correct information from other sources.[36] That is true, but it was attributable more to luck than good organisation that the engineers concerned happened to know the true layout of the pipework and had accurate information readily available to them[37] as well as the time and the means to provide it to those who needed it.[38]

It is important that all gas transporters have accurate maps of the pipelines serving buildings in multiple occupation.[39] Although Cadent has a process for revising its maps, it was not implemented in good time in the case of Grenfell Tower.[40] Accurate maps are essential in order that operatives can locate the pipeline isolation valves and may be of critical importance in emergencies. There appears to be no good reason why the map was not revised after the 2016 survey, or, failing that, after the installation and commissioning of the new pipe in early 2017.

UK designers of gas supply systems pay particular attention to the standards published by the Institution of Gas Engineers and Managers (IGEM) when planning and executing work of that kind.[41] Although gas engineers should be aware of the Building Regulations,[42] in 2016 there was a strong emphasis and reliance on IGEM publications and there existed within the gas industry a general understanding that if an engineer complied with that guidance, all relevant regulatory standards, including the Building Regulations, would be met.[43] The IGEM publication applicable to the work to be carried out at Grenfell Tower in 2016 was IGEM/G/5, second edition.[44]

Having cut and capped the riser serving the “Flat 2s” on 1 October 2016, Cadent had to consider whether and, if so, how, to reinstate the supply of gas to them.

For that purpose it engaged tRIIO, a consortium formed by Morrison Utility Services Limited and Skanska Construction UK Limited, to design and install replacement gas pipes and connections.[45] tRIIO entered into subcontracts with other organisations and individuals for some of the work.[46] There was plainly some urgency and it is apparent that Cadent sought to reinstate customers’ gas supplies as quickly as possible.[47]

Two options were available to it: it could either find a way to install a new riser to reconnect the “Flat 2s”, or it could pay customers to replace their gas appliances with electric appliances. On 17 November 2016, Cadent rejected the latter option because only part of the building was affected.[48] It therefore decided to restore the supply of gas, provided it could do so safely.[49]

IGEM/G/5 provides a hierarchy of options for siting gas pipes. It states that the best option is an external network of pipes so as to give them direct ventilation to natural air.[50] In the case of Grenfell Tower however, the TMO and tRIIO agreed that installing pipes on the outside of the tower was not practicable because they would pierce the newly installed rainscreen cladding, would compromise the integrity of the facade and potentially invalidate any warranty for the cladding system.[51] In our view, that was a reasonable position for the TMO to take.

tRIIO commissioned Simon Boygle, a surveyor trading under the name of London Ops Gas, to find an alternative route for a replacement riser. He and tRIIO considered several options, including running the new riser in the same place as the original riser, that is, vertically through the floors and ceilings of the flats and directly into the kitchens. That idea was quickly discounted as impracticable, however, because of the difficulties involved in obtaining access to the pipes embedded in the fabric of the building.[52] They also considered running the new pipe through the existing utilities shaft,[53] but that option was rejected, principally because the ventilation was considered to be inadequate.[54]

A key consideration was that any gas pipework must be adequately ventilated so that if a leak occurs it does not cause the atmosphere to become unsafe, with the consequent risk of an explosion. While external ventilation directly to fresh air is preferred,[55] IGEM/G/5 allowed for any steel pipeline that had welded or screwed joints to be ventilated indirectly to outside air through an area that was “normally-occupied”, meaning occupied as an individual dwelling or a common corridor or lobby.[56] However, IGEM/G/5 stated that mechanical ventilation should not be used to achieve the required ventilation level,[57] which in the case of Grenfell Tower prevented siting gas pipes in the lobbies, since they relied on mechanical ventilation. IGEM/G/5 also required ventilation to be provided at the top and bottom of every fire compartment,[58] consistently with the guidance in Approved Document B relating to ventilation in protected shafts.[59] Approved Document B also provided further guidance on the ventilation of shafts, directing the reader to BS 8313:1997 on the size of ventilation openings.[60]

It is clear that there were two requirements that had to be taken into account: ventilation for gas safety and compartmentation for fire safety. Giving appropriate recognition to each of them is a challenge for anyone seeking to supply gas to any complex building in multiple occupation.

On 12 October 2016 Simon Boygle proposed that a new riser should be installed in the stairwell of Grenfell Tower.[61] That was the only means by which to satisfy the twin requirements of ventilation and compartmentation.[62] The new riser would travel from the basement, through the lower floors, through the stairs, and then by means of laterals restore the supply of gas to the “Flat 2s”. It was envisaged that at a later date the pipework would be extended to serve all the flats in the tower and the original pipework would be decommissioned.

What nobody involved in the project understood at the time was that although both IGEM/G/5 and Approved Document B allowed gas risers to be placed in protected stairs,[63] if the stairs were also firefighting stairs, additional protections were required.[64] Diagram 52 in Approved Document B advised that firefighting stairs should be constructed in accordance with BS 5588-5:2004,[65] which in turn advised that such a shaft should contain only services associated with fire-fighting. In other words, the guidance in Approved Document B and the British Standard to which it referred was that gas supply equipment should not pass through the same compartment as services associated with firefighting.[66] Although it is arguable that appropriate standards of safety could have been achieved by separating the riser from the firefighting stairs with fire-resisting construction, as was explicitly permitted for gas pipework in protected stairs,[67] the position is not clear in the guidance document or standards in relation specifically to firefighting stairs. We note that the first design did not have any boxing protecting the riser in the stairs.

That special consideration had to be given to firefighting stairs does not appear to have been widely understood in the gas industry before the Grenfell Tower fire[68] and there is no evidence that any other professional expressly considered the point.[69]

tRIIO’s first design did not provide much detail of how the ventilation of the pipework would be achieved.[70] The riser was to be constructed of steel with welded joints, so indirect ventilation was available as a design choice pursuant to the guidance in IGEM/G/5.[71] On that basis the design included the following features:

No analysis was made of the ventilation available for each space through which the gas pipes were to pass.[77] In our view, such a complicated design required detailed consideration of the ventilation arrangements in order to demonstrate that the pipework would be ventilated adequately and safely.[78] tRIIO did not carry out a detailed analysis of that kind.

A detailed risk assessment should also have been carried out.[79] According to IGEM/G/5, designers of gas pipework in buildings in multiple occupation should carry out a risk assessment to identify and mitigate hazards and maintain a written record of the results.[80] In late 2016 tRIIO’s procedure was to record risks in its CDM Design Risk Register, which took the form of a spreadsheet that generated an initial risk score. If that score was 18 or more, tRIIO would carry out a fuller assessment by responding to a list of more probing questions.[81] tRIIO completed the CDM Design Risk Register in relation to Grenfell Tower on 15 November 2016. It generated a score of 17.[82] Although the designers could have manually over-ridden the process and carried out a fuller assessment of risk, they did not do so.[83]

We do not think that tRIIO’s risk assessment process was adequate for buildings in multiple occupation.[84] We note that tRIIO’s own CDM Design Risk Register shows that any building of that kind would be “high risk” in and of itself[85] and accordingly, the process should have required that it be the subject of a fuller assessment. That was particularly so in the case of an old building such as Grenfell Tower in circumstances where the proposed design was relatively complicated. tRIIO should therefore have overridden the scoring system and considered the risks posed by the installation in more detail. Mr Dolan, tRIIO’s director of operations, accepted that it had been at fault in failing to do so.[86]

Cadent’s contract with tRIIO did not require it to check design decisions and it did not expect to do so. However, once work began, Cadent was under a statutory duty to notify the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) using the form “F10”.[87] tRIIO had produced an F10 covering all the work it intended to carry out during the period 2016-2017,[88] but that did not constitute an adequate notification of the work at Grenfell Tower. Cadent should have produced an F10 to notify the HSE of that work.[89] A generic F10 of the kind produced by tRIIO was inappropriate for a project affecting a large building in multiple occupation.[90]

Over the course of some months the original riser was replaced using a new pipe which entered the basement below ground level on the east side.[91] From there it passed up through the lower floors and into the stairwell where it passed through holes cut in the floors of the landings.[92] If the supply of gas was to be restored to a flat, a horizontal pipe, or ‘lateral’ was led from the riser through the stairwell wall and into the lobby.[93] The lateral then passed round the perimeter of the lobby just below the ceiling and a pipe from it entered the relevant flat through a hole in the wall between the flat and the lobby.[94] The pipe was connected to a meter which had to be moved from its original position in the kitchen to the hallway near the front door.[95] Further pipework was then installed between the meter and any kitchen appliances that burned gas.

After the gas pipework had been installed into the tower it was commissioned on 10 March 2017,[96] even though the work in the lobbies of boxing it in had not been completed. At that stage the work did not comply with the guidance in IGEM/G/5 because a leak in the lobby would have been ventilated by mechanical ventilation, which was not permitted. It appears that tRIIO took a calculated risk and reconnected the supply of gas to customers before all the work had been completed. We understand the desire to reconnect occupants as quickly as possible, but the fact remains that tRIIO should not have introduced gas into a pipeline without all the ventilation requirements being in place.[97]

On 21 March 2017, tRIIO’s design manager inspected the work and noted that flanged joints had been installed rather than welded joints.[98] Flanged joints have a compression fitting which seals the connection between the two pipes with a gasket, as opposed to screwing or welding the pipes together.[99] As a result, flanged joints are more prone to leaking and could not be used if the stairwell was to provide the necessary ventilation.[100] The installation of the flanged joints compromised the ventilation strategy and the error was not noticed by tRIIO’s design team before gas was reintroduced into the pipeline.[101]

On 24 March 2017, in response to that discovery, tRIIO introduced a modification to the arrangement, under which the vertical riser (as well as the laterals) was to be fully boxed-in, both in the stairwell and also throughout the lower levels and the basement, using materials with a two-hour fire rating.[102] Intumescent vents were to be installed in the boxing in the stairwell, which would close in the event of a fire but allow for some ventilation in normal circumstances.[103]

The description of the modified arrangement did not show how the boxing-in was to be achieved at the lower levels, i.e. through the utility duct and in the storeroom and basement. Nor did it show how the boxing-in would be connected to the vent in the roof.[104] Moreover, the new design created other problems in relation to ventilation. It assumed that air would circulate within the boxing and across the pipework through the holes in the landings and the walls between the stairwell and the lobbies, but the holes through the landings had not been enlarged to allow for a flow of air within the new boxing.[105] There was no evidence that calculations had been carried out to determine the size of the holes that would be required nor was it clear how an increase in the size of the holes and the boxing could be accommodated given the narrowness of the stairs.[106] The use of intumescent vents was not consistent with the requirements of IGEM/G/5.[107]

In this case tRIIO manually over-rode its CDM Design Risk Register process and carried out a full design risk assessment that was recorded on a four-page spreadsheet identifying factors for consideration.[108] Three of those factors related specifically to buildings in multiple occupation, namely, breach of compartmentation, failure due to thermal expansion of south-facing pipes, and ventilation.[109] They were appropriate matters but they did not cover everything that a designer ought to consider, such as, for example, means of escape in fire, corrosion, inspection and maintenance, and valve access and security.[110]

In addition, the information tRIIO added to the Design Risk Register lacked sufficient detail. On the important question about fire compartmentation, the action recorded was simply to follow the Building Regulations and Fire Safety Order and seal the compartments accordingly. A gas engineer was to review the arrangements for ventilation, although they were not described in any detail in the design. Mr Dolan accepted that the assessment process fell below the standard required and that a more detailed consideration of matters affecting buildings in multiple occupation was needed.[111]

Although tRIIO adopted a more formal approach to the modified arrangement, there is no evidence that anyone calculated the amount of ventilation needed for the pipework.[112] That was particularly important, given that the ventilation strategy had changed and that the degree of ventilation had been reduced by the boxing-in of the entire pipeline.

Regrettably, tRIIO and its sub-contractors continued to make mistakes during the construction of the work. As Mr Dolan and tRIIO accepted,[113] although the boxing-in of the pipework should have been carried out using two-hour fire-rated materials[114] (and although the TMO was told that it would be),[115] the sub-contractors, Express Building Contractors Ltd, in fact used materials that were rated as having a fire integrity of only 88 minutes.[116]

A further problem also arose from the need to move the gas meters from the kitchens closer to the front doors because tRIIO’s specifications required that there be no more than two metres of service pipework inside a residential property.[117] As a result, a sub-contractor of K&S Pipe Contractors, Holland Gas Engineers Ltd, was obliged to place meters in or adjacent to the entrance hall, which was the only escape route.[118] Meter points can present a particular fire risk because if there is a fire, gas can burn freely from open meter ends. IGEM/G/5 suggests relatively easy mitigations, including installing the meter inside a 30-minute fire-rated cupboard with a self-closer or installing a thermal cut off device[119] to stop the flow of gas either before or after the emergency control valve.[120] However, neither of those steps were considered at Grenfell Tower.[121]

tRIIO maintained that the meters were often sited in an alcove or cupboard adjacent to the entrance hall and that the mitigation measures mentioned above were unnecessary.[122] However, we have seen examples of meters being located behind curtains[123] or behind doors that had rising hinges and were not self-closing[124] and it is plain that in some cases the meter was sited close to the escape route from the flat. Although there is no evidence that any of the meters played a role on the night of the fire, we do not consider those arrangements to have been satisfactory.

There is no evidence that gas leaked from any part of the new installation during the fire on 14 June 2017.[125] However, the works had not been completed by that time. The boxing-in in the stairs had almost been completed, with only the top floor and the connection to the roof vent outstanding, but the boxing-in of the laterals in the lobbies had not been completed, except on floor 5. Battens had been installed for the boxing-in in the lobbies on floors 4, 8, 9, 10 and 11 only. Mr Dolan estimated that the remaining work would have taken about five weeks.[126]

While the work was being carried out the oversized holes between the stairwell and the lobbies were not temporarily fire-stopped. It was possible, therefore, for smoke to move from one compartment space to another. Heavy smoke staining on the internal faces of the boxing in the stairs indicates that some smoke must have travelled from the lobbies into that boxing.[127] There was also evidence of staining between adjacent floors which appears to indicate that smoke had travelled between floors through the boxing of the riser.[128] It is possible, therefore, that during the fire smoke may have travelled from one lobby into the boxed-in riser and out into lobbies on other floors higher up the tower, thereby compromising the compartmentation between the lobbies. It is not possible, however, to know how much smoke may have travelled in that way or at what stage in the fire. We think it is likely to have been a much less significant route of smoke spread than open fire doors between the lobbies and the stairs.

In March 2017 Cadent expressed concern to tRIIO about the oversized holes between the lobby and the stairwell, which it thought might create an unsafe situation in the event of a fire.[129] In those circumstances we think that tRIIO should have made sure that those holes were temporarily fire-stopped while the work remained incomplete,[130] as Mr Dolan accepted.[131] We are unable to tell whether the failure to do so had any adverse consequences on the night of the fire, but we think it important to record that the risks should have been identified and mitigated during the work.

One question we thought it appropriate to consider is whether the work involved in the replacement of the gas riser required building control approval. In 2016, the gas industry did not routinely consult building control in relation to reinstatement work.[132] In this instance, although Carl Stokes advised that the work was notifiable,[133] tRIIO did not consult building control because it thought that the work did not require approval, despite the material changes to compartmentation that the riser design entailed.[134] In March 2017 Janice Wray told John Allen, the head of RBKC’s building control department, that the new riser had been installed in the staircase and invited him to send a team to the site to look at the work.[135] However, he told her that the riser works were regarded as a repair and were a matter for a fire risk assessment.[136] tRIIO, for its part, appeared to believe that, if carried out in accordance with IGEM/G/5, the work would comply with the Building Regulations but that the TMO would make any necessary application for building control approval.[137]

Whether the work of replacing the gas riser required building control approval is a difficult question on which the evidence does not enable us to express a clear conclusion. However, we think that in cases where the structure of a building on which effective compartmentation depends is affected by the replacement of existing services, careful consideration should be given to the need to obtain building control approval as well as complying with any relevant industry guidance.

In chapter 7 of his Phase 1 report the chairman described the statutory responsibilities, structure and organisation of the London Fire Brigade (LFB). In particular, he described in some detail the operation and management of the control room, the systems and procedures employed in it and the method of handling emergency calls. Later in the same chapter he described operations at the incident ground, with particular emphasis on the role and responsibility of the incident commander and support available from monitoring officers and command units. It is not necessary for us to repeat any of that in this report.

In that report the chairman expressed the view that there had been significant shortcomings in the way the LFB had responded to the fire at Grenfell Tower, both in the control room and on the incident ground, many of which were the result of a failure to provide its control room officers and firefighters at all levels with the skills, preparation and training needed to enable them to respond effectively to the situation they faced. He therefore considered it necessary in this second phase of the Inquiry to examine the organisation and training of the LFB in the years preceding the fire with a view to understanding how that situation had come about and how it might be avoided in the future.

We begin this Part of our report with a brief description of the way in which the management of the LFB is organised to enable the reader to understand the complicated structure that existed in the years immediately before the Grenfell Tower fire. That structure is of importance only because it sheds light on the way in which the organisation functioned during that period. We follow that with a description of the way in which training was organised and training packages obtained from the LFB’s provider, Babcock. It was essential to train officers at all levels in order to meet the challenges of incident command and to ensure that operations were conducted effectively. In view of the criticisms of the LFB made by the chairman in his Phase 1 report we considered it appropriate to pay particular attention to that aspect of the brigade’s management, particularly since it had been the subject of a specific recommendation by the coroner who conducted the inquests following the Lakanal House fire.

Although the fire at Lakanal House in 2009 emphasised the dangers posed by the use, especially in high-rise buildings, of certain kinds of materials and methods of construction, the sources of that knowledge had been available for some years. We therefore decided that we should investigate the extent to which the LFB had been aware of those dangers and, if so, how widely the information had been shared within the organisation. We have also considered other sources of information that were available to it in order to understand why the dangers of a loss of compartmentation and the rapid spread of fire were not understood or recognised by operational station crews.

One important aspect of preparation is gathering information about buildings that may present particular challenges. The LFB is unusual in having a large number of high-rise buildings in the area for which it is responsible, many of which pose particular challenges. We have therefore examined and report on the steps taken by the LFB to collect information about buildings, particularly those that may present particular challenges in the event of a fire.

The response of the control room to the huge volume of information it received as a result of the fire made it necessary for us to examine the quality of the training delivered to control room staff during the years leading up to it. That in turn required us to examine the way in which the control room had been managed and the importance attached to the delivery of regular training, particularly in handling calls from or about people trapped in high-rise buildings. In this Part, therefore, we set out our findings on those matters.

There are other aspects of the response to the fire that in our view called for examination. One significant obstacle encountered by the firefighters who entered the tower was the difficulty of maintaining effective radio communication. We have therefore considered the nature of the equipment then in use, the source of the difficulties in maintaining communication with the bridgehead and the steps that might be taken to overcome them in future.

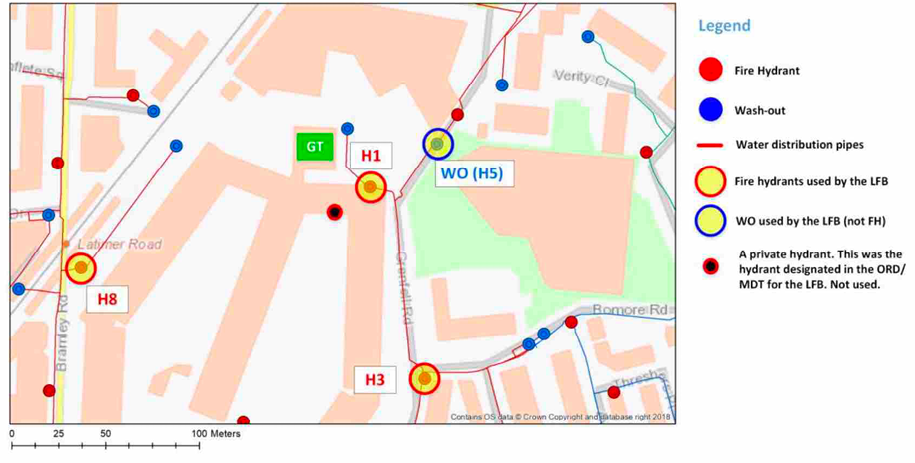

Maintaining an adequate supply of water also presented difficulties. We have therefore examined the means by which water is made available for firefighting and the steps that were taken by the water undertaker, Thames Water, to improve the supply while the fire was being fought. We have also considered the equipment available to firefighters to deliver water at the fireground and the way in which it was used during the course of the fire.

This chapter provides a broad overview of the organisational structure of the LFB in the period leading up to June 2017. It is necessary to be aware of the key elements of that structure in order to understand which departments and individuals were responsible for different aspects of its functions before and at the time of the Grenfell Tower fire.

On 1 October 2007, Ron Dobson was appointed LFB Commissioner, a position which he held until his retirement on 31 December 2016.[138] Following a period of handover from September to December 2016, Dany Cotton was appointed interim Commissioner on 1 January 2017 and subsequently appointed to the substantive rank on 14 June 2017.[139] The permanent appointment on 14 June had been planned and was unrelated to the Grenfell Tower fire.[140]

The London Fire and Emergency Planning Authority (LFEPA) was abolished on 1 April 2018 and replaced by the London Fire Commissioner, who became the fire and rescue authority for Greater London. The London Fire Commissioner assumed responsibility for LFEPA’s statutory obligations under the Fire and Rescue Services Act 2004 outlined above.[141] On 31 December 2019, Ms Cotton retired as Commissioner and was succeeded by Andrew Roe on 1 January 2020.

As an organisation the LFB was divided into three directorates, the heads of which reported directly to the Commissioner and were responsible for a number of different departments. The internal structure of the directorates was complex and subject to frequent changes, most notably in 2015 following a wide-ranging reorganisation of the LFB as a whole. In the following paragraphs we give a broad and simplified description of the LFB’s structure before and after 2015, focusing on the departments and functions which are most relevant to the Inquiry’s investigations.

Before 2015, the LFB’s three directorates were the Deputy Commissioner’s directorate, the Directorate of Operational Resilience and Training (together sometimes known as the two operational directorates) and the Directorate of Financial and Contractual Services.

Rita Dexter served as Deputy Commissioner between November 2009 and March 2015.[142] In addition to deputising for the Commissioner, the Deputy Commissioner was responsible for the following departments within her directorate: Operational Prevention and Response, Fire Safety Regulation, Strategy and Performance, Communications, and Legal and Democratic Services.[143] The first three of those departments are relevant to the Inquiry’s work.

The Operational Prevention and Response department[144] was responsible for the planning, direction and delivery of the LFB’s operational service, mobilising crews and community safety,[145] including overall responsibility for the control room, fire stations and the collection, management and use of operational risk information.[146] At all relevant times, the LFB’s 102 fire stations were grouped by the 33 London boroughs in which they were located,[147] each headed by a Borough Commander. The boroughs were in turn grouped into four Areas (North East, North West, South East and South West) each headed by an Area Deputy Assistant Commissioner (DAC). Before 2012, many of the department’s responsibilities were split geographically between North London and South London, each headed by an Assistant Commissioner (AC). However, from June 2012 the role and responsibilities for the whole of London were brought together under a single Head of Operational Prevention and Response.

The Fire Safety Regulation department had two broad functions: Regulatory Fire Safety and Community Safety. The Regulatory Fire Safety arm of the department was headed by two DACs, who filled the roles of Head of Fire Safety Delivery and Head of Fire Engineering and Specialist Fire Safety.[148]

Fire Safety Delivery included the department’s fire safety teams, which had responsibility for managing the LFB’s audit and enforcement activities under the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005 (the Fire Safety Order). As with the Operational Prevention and Response department, the Fire Safety Delivery arm of the department was split into the same four geographical London areas, each headed by an Area Fire Safety Manager, and further divided by boroughs.[149] Fire Safety Delivery was responsible for the LFB’s programme of fire safety audits carried out by fire safety inspecting officers, who could be from either operational or non-operational backgrounds.[150] Some fire safety inspecting officers received additional training to enable them to act as fire engineering liaison officers, who provided support to the more specialist fire engineering teams in relation to building control consultations.[151] Fire Safety Delivery included the Fire Safety Enforcement team, headed by Andrew Jack, which was responsible for reviewing enforcement notices produced by inspecting officers, interpreting legislation and overseeing enforcement prosecutions.[152]

Some senior operational officers were also senior fire safety officers. Senior fire safety officers were typically station managers or group managers who were not part of the Fire Safety department but who would be mobilised to attend incidents requiring four or more pumps to provide support to the incident commander.[153] They undertook a relatively broad, short training course in the basic principles and practice of fire safety to enable them to fulfil that role.[154] In practice, and as happened at Grenfell Tower,[155] it was common for officers who were mobilised to incidents as senior fire safety officers to be assigned different roles by incident commanders.[156] AC Daly, sometime Head of Fire Safety, said that, in his view, this practice of re-assigning senior fire safety officers to operational roles reflected a failure to give priority to fire safety expertise on the incident ground.[157]

The Fire Engineering and Specialist Fire Safety arm of the department included its more technical fire safety teams, such as the Fire Investigation and Fire Engineering teams. Fire Engineering, also known as the Fire Engineering Group, comprised a team of around 10 specialist fire engineers who held, or were studying for, degree-level qualifications in fire engineering.[158] Led by two Senior Fire Engineers, the group’s main function was to consider complex references from building control bodies that were beyond the experience of inspecting officers.[159] Most of the group’s work consisted of providing support to external bodies, though the group also contributed to the development of LFB policy as part of the standard process of internal consultation.[160] Fire Engineers were not involved in the development of operational training unless they were specifically asked to contribute their expertise.[161]

The Fire Investigation team was made up of watch-based operational personnel whose function was to attend incidents to investigate the cause of the fire. The team used the information collected from such inspections to identify trends with a view to informing activities within the LFB and to advance the work carried out by the LFB with external bodies, including those in industry, to improve fire safety across the built environment.[162]

The other arm of the Fire Safety department, Community Safety, concentrated on actions designed to prevent fires (such as home safety visits), on people at particular risk and on community behaviour.[163]

The Strategy and Performance department led the LFB’s work relating to the integrated risk management plan (the London Safety Plan), its internal risk management planning, and performance reviews.[164] Despite its name, the department was not in fact central to the strategy or performance of the LFB’s core operational responsibilities.

AC Gary Reason was appointed Director of Operational Resilience and Training in January 2012.[165] On his retirement in January 2015, he was succeeded by AC James Dalgleish.

The Directorate of Operational Resilience and Training comprised the following departments: Operational Procedures, Operational Assurance, Operational Resilience, and Human Resources and Development.

The Operational Procedures department was responsible for the creation and maintenance of the vast majority of the LFB’s operational policies,[166] subject to certain exceptions, such as the Incident Command policy, for which Operational Assurance was responsible.

The Operational Assurance department was primarily concerned with ensuring effective incident command, the safety of operations and the management of risks on the incident ground.[167] Dany Cotton, who headed the department from its inception in 2012 before her term as Commissioner, said that it was designed to provide combined and streamlined leadership of two existing LFB functions, the Operational Review team’s quality assurance of incident ground operations, and the Health and Safety team’s learning from incidents to identify risks to LFB staff.[168] The department was responsible for producing six-monthly reports which identified risks and trends from an analysis of a wide range of sources, including the LFB’s Incident Monitoring Process Database (IMPD), significant incidents, incident accident reports, fire investigation reports, training and sources from outside the LFB.[169] The department was also responsible for overseeing the production of articles for Operational News, the LFB’s internal circular, by which it sought to draw the attention of staff to some of the risks it had identified and any lessons to be learnt.[170] The functions of the Operational Assurance department were such that it was ultimately responsible for ensuring the operational effectiveness of the LFB and for ensuring that LFB staff were aware of, and adequately prepared to deal with, operational risks which might affect their safety.

Key teams within the Operational Assurance department included the Incident Management Policy Group (also known as the Incident Command Policy Group), which was responsible for collating the information from the sources mentioned above and producing the six-monthly reports for the Operational Directorates Co-ordination Board (the co-ordination board),[171] and the Operations Review Team, which provided oversight of the LFB’s operational activities and routine training designed to maintain and develop operational skills.[172]

The Operational Resilience department included contingency planning and a special operations group focused on policies, procedures and the provision of equipment related to terrorism.

The Human Resources and Development department, previously the Training department, was responsible for the management of the LFB’s contract with its external operational training provider, Babcock Training Limited (Babcock), as well as the LFB’s human resources function.[173] The LFB’s operational training structure and the adequacy of particular aspects of the operational training that existed at the time of the Grenfell Tower fire, is covered in more detail below. The training of control room staff, which was not included in the Babcock contract, is covered separately in Chapter 78.

The Directorate of Finance and Contractual Services, led by Sue Budden, carried out the LFB’s non-operational functions, including Financial Services, Information and Computer Technology and Procurement. It is, on the whole, not relevant to the work of the Inquiry.

Before 2015, the title of Third Officer was held by a senior operational officer in addition to their day-to-day responsibilities. Its purpose was to ensure that there were three senior uniformed officers (the Commissioner, the Director of Operational Resilience and Training, and the Third Officer) able to provide operational cover for serious incidents. From 2010, the position of Third Officer was held by David Brown, who was then an Assistant Commissioner.[174]

In 2015, the LFB underwent an internal reorganisation and the rank of Deputy Commissioner was dropped. Commissioner Dobson said that the position was no longer required as the directors were able to deputise for him within their own areas of responsibility. In broad terms, the Deputy Commissioner’s directorate was reorganised into a new Directorate of Operations. The former Directorate of Operations, Resilience and Training was renamed the Directorate of Safety and Assurance, and the Directorate of Finance and Contractual Services continued as before. In addition to some internal restructuring within each directorate, some departments and functions were moved between directorates.

The separate role and title of Third Officer also ended, as there were now three senior uniformed officer positions: the Commissioner, the Director of Operations and the Director of Safety and Assurance.

The newly created Directorate of Operations retained responsibility for many of the departments which had previously reported to the Deputy Commissioner.

The Fire Safety Regulation department, now simply called “Fire Safety”, continued to incorporate the LFB’s fire safety (including Fire Safety Enforcement and Fire Investigation), fire engineering and community safety functions.

The operational firefighting and control functions of the previous Operations, Prevention and Response department were divided between two new departments: Fire Stations and Central Operations and Control and Resource Management.[175]

AC Brown was appointed Director of Operations in April 2015. When he retired on 31 March 2017, he was succeeded by DAC Philip Thomas George (known as Tom George).[176]

The newly renamed Directorate of Safety and Assurance continued to include Operational Procedures (re-named Operational Policy), Operational Assurance, and Operational Resilience. The Human Resources and Development department was renamed Development and Training, with its human resources functions moved to the Legal and Democratic Services department within the Directorate of Finance and Contractual Services. Health and Safety and the Operational Review Team, previously sub-departments of Operational Assurance, now reported directly to the Director.

Following the restructuring, on 1 December 2015 AC James Dalgleish assumed the position of Director of Safety and Assurance on an interim basis before Dany Cotton’s appointment as Commissioner.[177] Upon Ms Cotton’s appointment, AC Stephen Apter became Director of Safety and Assurance in December 2016. He was in post on 14 June 2017.[178]

This section describes the principal LFB boards and committees which existed before and after the 2015 restructuring.

The Corporate Management Board was the LFB’s highest-level committee, with a membership comprising the Commissioner, the three directors and some heads of department, with other officers and advisers attending when required. The Corporate Management Board held regular meetings and provided a forum for the LFB’s most senior officers to discuss operational, managerial and strategic matters. It also reviewed key papers and reports before they were submitted to the LFEPA Strategy Committee for oversight.[179]

There was also a smaller, informal leadership group known as “the Commissioner’s Group”, consisting of the Commissioner, the three directors and, before the 2015 restructuring, the Third Officer. The Commissioner’s Group met about once a week for informal meetings, which were not minuted, to share information with the aim of improving communications between the Commissioner and the directors.[180] Commissioner Dobson said that his day-to-day management and oversight of the directors was not exercised through the Commissioner’s Group, but by daily individual meetings and, more formally, at the Corporate Management Board.[181]

The Operational Directorates Co-ordination Board (the co-ordination board) comprised the directors and most of the senior officers and heads of department in the LFB’s two operational directorates. It comprised the heads of Operational Prevention and Response, Fire Safety Regulation, Operational Procedures, Operational Resilience and Human Resources and Development (the training department). The control room was not represented. Until 2015 the co-ordination board was chaired by the Deputy Commissioner, Rita Dexter; following the restructuring in 2015 it was chaired by AC Brown in his capacity as Director of Operations. The Commissioner was not a member of the co-ordination board and did not attend its meetings.[182]

The primary function of the co-ordination board was to provide a forum in which the two operational directorates[183] could discuss and co-ordinate their activities, identify risks to operational staff and identify and recommend training required in response to such risks.[184] Trends and lessons identified by the Operational Assurance department were brought to the co-ordination board for discussion. The co-ordination board would then select the most significant operational topics for development into paper or computer-based training.

In late 2016, the name of the co-ordination board was changed to the Operational Professionalism Board[185] but that had no effect on its working.

In the Phase 1 report, the chairman found various shortcomings in the LFB’s training, which were revealed in its response to the fire, both on the fire ground and in the control room.[186] In this phase of the Inquiry, therefore, we have examined the way in which the LFB identified training needs (particularly those arising from incidents), its approach to the procurement and provision of training and its systems for monitoring the effectiveness of training.

The LFB had a complex system for identifying the need for training and delivering training to staff at various levels. A process known as the dynamic and intelligent operational training (DIOT) process was central to the operation of that system. Its purpose, as described in Policy No. 825 (PN825), was to monitor operational, health and safety and training performance, to identify trends and provide mechanisms to support the maintenance of competence on the part of operational staff.[187] As Deputy Commissioner Dexter agreed, that somewhat complex description could fairly be summarised as learning from mistakes made in fighting fires and promoting good practice.[188] Its principal purpose, and that of the co-ordination board more generally, was to identify risks to operational staff and to provide appropriate training.[189] The process could also, in theory, result in the amendment of an existing policy or the introduction of a new policy, but PN825 described that outcome as rare.[190] Ensuring that the objectives of the process were achieved was the main responsibility of the co-ordination board.[191]

Central to the process were the arrangements for monitoring incidents and the creation of the associated database described in PN825. The database was used to record comments on the performance of operational personnel or the brigade as a whole during incidents and training.[192] Such comments, often referred to as “development points”,[193] typically emerged from meetings held after operational incidents or training exercises specifically to consider the quality of the response and the performance of the incident commanders.[194] PN825 made it clear that entries should be made on the database only in cases where the performance of an individual, team, piece of equipment or the organisation as a whole had fallen below the required standard or had exceeded expectations.[195]

Except in the case of monitoring officers, who were required to post comments on the database in certain cases, firefighters of all ranks could post comments if they wished to draw attention to something they considered to be of importance in relation to the operational response. (Comments made as a result of meetings to consider the performance of incident commanders were posted on the database in all cases.)

The Incident Management Policy group, which was part of the Operational Assurance directorate, was responsible for analysing the database and producing six-monthly reports to the co-ordination board identifying significant trends and matters that required attention.[196]

Although the system could be used by firefighters of all ranks, DC Dexter and Commissioner Cotton agreed that few firefighters made use of the opportunity to make comments.[197] One biannual incident monitoring report in 2014 shows that entries were made in respect of only 4% of the 47,105 incidents recorded[198] and it follows that 96% of incidents during that period generated no comments at all. The report indicated that those figures represented an increase on previous quarters, when the use of the system must have been even lower.

Commissioner Cotton and Dr Sabrina Cohen-Hatton, head of the Operational Review Team in June 2017, said that operational staff, especially incident commanders, saw development points as negative.[199] Ms Cotton also said that both firefighters and officers found it difficult to accept criticism of their operational performance[200] and Deputy Commissioner Dexter said that some staff had voiced fears that they might get into trouble if they admitted having done something wrong.[201]

Commissioner Cotton said that she saw no connection between the negative perception of development points and the less than enthusiastic use of the system.[202] On the other hand, Deputy Commissioner Dexter told us that the negative perception of development points was the main reason given for not posting comments.[203] That is the most plausible explanation we were given for the significant under-use of the system. The LFB did attempt to improve the use of the database by seeking to reassure staff that development points were not intended to be punitive and by informing officers of the importance of posting comments, but its efforts were unsuccessful.[204]

The low use made of the monitoring process and the very low proportion of incidents which gave rise to development points (even allowing for the fact that many of them were very minor) meant that the database was very narrow and could provide the co-ordination board with only a limited picture of operational trends or training needs. The process concentrated too much on identifying long-term trends, with the result that a serious problem disclosed by a single significant incident could be missed.[205] For example, the database entry for the Shepherd’s Court fire in 2016, a significant incident involving the spread of fire across the combustible facade panels of a high-rise residential block and a partial evacuation, failed to identify the spread of fire across external walls or the use of combustible panels as matters to be considered.[206]

Deputy Commissioner Dexter accepted that the incident monitoring process fundamentally relied on the willingness of individual officers on the ground to provide information and that, in the context of a falling number of incidents, the amount of information available to it was steadily diminishing.[207]

On receipt of a six-monthly database report, the co-ordination board considered whether any training was required in response to what it disclosed. Training was delivered primarily in the form of articles published in Operational News, the LFB’s internal information circular, some of which were accompanied by computer-based training packages. Indeed, Operational News and its associated training packages were the main focus of the co-ordination board’s work.[208] Commissioner Cotton estimated that only half to two thirds of the operational trends identified in the database reports were in fact chosen as subjects for articles in Operational News.[209]

The Incident Management Policy group was responsible for producing articles for publication in Operational News, although the articles themselves were drafted by experts from the relevant departments before being reviewed and approved by Operational Assurance.[210] They typically took the form of a summary of an existing policy, drawing firefighters’ attention to its contents. Babcock produced reports every six months, in conjunction with the Human Resources and Development department, telling the co-ordination board how the training it was providing had been, or was being, improved to support the topics covered in the previous edition of Operational News. In many of those reports Babcock simply stated that the topics in question were already adequately covered.[211]

Commissioner Cotton said that summarising an existing policy in Operational News did not amount to training but had been intended to raise awareness and provide personnel with links to the associated training delivered through fire stations.[212] Initial training was provided to firefighters by Babcock, but the subsequent development and maintenance of operational skills was mainly carried out at station level in accordance with the Policy No. 427 (PN427) by means of computer-based training packages and lectures delivered by watch managers, attendance at which was recorded on crews’ training records.[213]

Watch managers were not provided with any centralised training materials for their lectures (apart from the policies themselves); instead, it was the responsibility of each watch manager to develop their own lectures and deliver them to crews.[214] For at least five years preceding the Grenfell Tower fire watch managers were given no guidance on how to deliver training and there was no process to ensure that officers who provided training were competent to do so.[215] Station-based training was monitored by Training Review Information Officers, who were responsible for ensuring that training was provided and that training records were complete and accurate.[216] But we have seen no evidence that any assessment of the quality of station-based training was carried out by those officers or anyone else.

This station-based training was separate from the centralised training that was commissioned by the Human Resources and Development department (later known as the Training and Development department) and provided by Babcock. For ease of reference and consistency, we shall refer to the department simply as “the Training department”. The Training department made no contribution to the substance of station-based training and played no part in ensuring that adequate station-based training was provided.[217] Nor did the Training department have any process by which to ensure that station-based training was consistent with the training provided by Babcock, which the LFB’s Head of Training, Peter Groves, accepted created an obvious risk of injury.[218] Mr Groves said that responsibility for identifying and assessing any omissions from station-based training lay with the individual borough commanders to whom stations reported, but he accepted that, since 2012, borough commanders had not been trained in how to make such assessments.[219]

The Training department’s limited involvement in supporting, monitoring or assessing the quality of station-based training is surprising and difficult to justify. The importance of Operational News to the delivery of training meant that the LFB was heavily reliant on local crews, local station managers and particularly local watch managers for creating and providing the associated lectures. That clearly created a significant risk that the training that crews at different stations received differed in content and quality.

Commissioner Cotton accepted that articles in Operational News could never provide more than a high-level, cursory exploration of an operational topic.[220] She also agreed that the quality of station-based training depended entirely on the skills of individual watch managers.[221] The co-ordination board’s principal method of evaluating the effectiveness of that training was to see whether a particular problem featured in later incident monitoring reports.[222] Many of the reports considered by the co-ordination board indicated that it was difficult to teach some lessons, as evidenced by the fact that some problems kept recurring.[223] Although the reports occasionally noted improvements resulting from certain steps that had been taken (presumably because the number of development points relating to that topic had reduced), there was no system by which the co-ordination board could assess the effectiveness of articles published in Operational News or station-based training.[224] The co-ordination board’s approach, which lacked any active assessment of the effectiveness of its training interventions, was wholly inadequate. It was foreseeable that it might fail to identify or resolve significant problems and in any event could identify problems only after they had occurred with sufficient frequency or severity to be noted in one or more incident monitoring reports.

At a meeting held on 14 October 2013, the co-ordination board decided to carry out a fundamental review of the system, because it realised that the same shortcomings were repeatedly occurring. The review was to examine whether the right tools were available to the brigade for monitoring the effectiveness of training and what systems were used by other organisations. It was envisaged that it might lead to a review of the way in which the LFB responded to incidents. Ms Cotton, then AC Operational Assurance, was asked to lead the review.[225] In the event, however, it was not as fundamental or far-reaching as had originally been intended or as was required, and although it led to a number of recommendations, it did not result in any significant changes to the system for monitoring the effectiveness of training.[226] No one was able to explain why the stated aim of the review had not been met or why the opportunity to reform the existing arrangements had not been seized.[227]

In April 2012, the LFB engaged Babcock to provide centralised training to operational firefighters but retained responsibility for training non-operational officers, including the control room and the Fire Safety department. Shortly after being appointed as training provider, Babcock agreed to undertake a review of all the LFB’s training courses within the first three years of the contract. The LFB’s course review board, chaired by Director Reason, was responsible for considering and approving Babcock’s proposals.[228]

Although Babcock was responsible for creating and providing operational training packages, the LFB alone determined learning objectives and in practice provided much, if not all, of the expertise necessary for the production of the content. At all times it retained ultimate responsibility for training its staff and no training package could be provided by Babcock unless it had been approved by the LFB.[229] The systems and structures relating to the training provided by Babcock were entirely separate from those relating to station-based training.

Responsibility for managing the LFB’s relationship with Babcock lay with the Training department. The Training department had no role in identifying training needs, recommending new training or requesting changes to existing training. Those were the responsibility of other departments, known as “commissioning departments”. The Training department’s role was essentially administrative: it collated training needs and requirements received from other departments and organised the process by which they were ultimately translated into training by Babcock.[230]

The Training department had two teams. The Learning and Development Strategy team was responsible for managing the development of training packages and communicating with Babcock and the commissioning departments.[231] The Training Assurance and Business Relationship team was responsible for ensuring that Babcock provided the training that had been agreed and that it met the LFB’s learning and training objectives.[232]

Training was commissioned in accordance with a process known as the “training commissioning and alterations process” (TCAP). When a training requirement had been identified, the commissioning department completed a form identifying in broad terms what was needed.[233] Project managers in the Training and Professional Development team, in consultation with the commissioning department, then completed what was known as a “TCAP form” which built on the basic information provided in the training request by addressing practical aspects of both substance and implementation.[234] When the team was satisfied that it was correct, the form was submitted to a group consisting of representatives of both Babcock and the LFB’s Training department to check that the training would not have a detrimental effect on operational services.[235] Babcock could suggest additions or changes to training but did so only once in the period before the Grenfell Tower fire.[236]

The next stage of the process was the development of the substantive training. Babcock proposed and designed the content of the training package to meet the identified learning objectives, subject to the approval of the commissioning department.[237] Although it managed the commissioning process, the Training department did not play a part in designing the training itself.[238] Babcock usually produced three options for providing the training for consideration by the LFB, which then made a choice.[239]

When the training materials had been assembled, a pilot training course was developed (except for some computer-based training), which was attended by experts and representatives of the commissioning department to ensure that it met the LFB’s needs.[240] If the pilot course was considered satisfactory, it was necessary to obtain the commissioning department’s approval, confirmation from Babcock that the design was complete and approval from the Head of Fire Stations and the Training department for the provision of the training to operational staff.[241] At that point the training could be rolled out. Some training packages were either delayed or not released at all following the completion of a TCAP form.

A consistent theme of the evidence was that Babcock lacked the expertise required to develop appropriate training. As a result, the LFB frequently had to provide experts from within its own ranks to assist it, which was a significant drain on resources.[242] The problem was most acute at the start of the contract in 2012, particularly in relation to incident command training. It was therefore forced to rely on LFB officers to provide the necessary expertise, with the result that it was not always possible to implement much-needed changes to incident command training with sufficient urgency.[243] Babcock’s reliance on the LFB for expertise also delayed other areas of training, including training on the use of breathing apparatus and real fire training.[244]

Although Mr Groves considered that it was Babcock’s responsibility to secure the expertise it needed, he rightly accepted that, whatever its contractual arrangements with Babcock, the LFB ultimately remained responsible for ensuring that firefighters were adequately trained.[245]

A report by Ribband Starr Ltd, commissioned by the LFB after the Grenfell Tower fire, found that many within the LFB regarded the commissioning process as cumbersome and capable of causing significant delay in the design and delivery of new courses.[246] All the LFB witnesses who gave evidence about training were of that view.[247] We agree with their assessment.

We were told that all training courses referred to in the annual statement of training requirements produced by the Training department were audited separately at least once a year by the LFB and Babcock and that the results were discussed at monthly meetings between Babcock and the Training department to decide whether any change to a particular training course was needed.[248] The Inquiry has not seen any evidence of audits or discussion of their findings. In particular, there is no evidence that audits resulted in the creation or amendment of any training packages. If audits were carried out, they appear to have had no effect on the content of training.

PN825 refers to four levels of evaluation used by the LFB to assess the effectiveness of training. Level 1 involves the use of questionnaires seeking the opinions of those who have attended courses,[249] Level 2 gauges what trainees have learnt, Level 3 assesses whether trainees have been able to apply their new skills and knowledge to the workplace, and Level 4 considers the effect of the training on the organisation as a whole.[250] We were told that training courses, apart from computer-based training, had been subject to Level 1 evaluation but that no formal Level 3 or Level 4 evaluations had been carried out.[251]

There was no system in place for evaluating the performance of staff who had attended training courses by reference to previously agreed criteria. Once a training package had been developed by Babcock and approved by the commissioning department it was assumed to be suitable.[252] That might have been a reasonable approach if the LFB had implemented adequate arrangements to review the effectiveness of training courses, but it is plain that it had made no such arrangements. The approach was particularly unsound in circumstances where there was no process at all by which the Training department was able to review the overall effectiveness of a training programme.[253]

We have been left with the clear impression that, instead of adopting a system which measured the effectiveness of training by reference to previously agreed criteria, the LFB simply waited to see what, if any, problems subsequently arose at incidents. Such an approach might or might not reveal any deficiencies in training, but if it did, it was by then likely to be too late. The obvious weaknesses of that approach were aggravated by the fact that, as the number of incidents declined, progressively less confidence could be placed in a system that relied on problems being identified at incidents.[254]

The procedure adopted by the LFB for commissioning training in the years leading up to the Grenfell Tower fire placed much emphasis on ensuring that the right courses were produced and that training did not interfere with operational requirements. Both were laudable aims. However, the process was very cumbersome and inevitably led to excessive delay in providing new courses. There was also a disturbing absence of any system for evaluating the effectiveness of courses once they had been introduced. At a local level too much responsibility was placed on watch managers to devise and deliver training, with insufficient support and oversight. Since the quality of training at that level depended to a considerable extent on the skills of individual watch managers, the quality was bound to be variable.

In the Phase 1 report the chairman found that the incident commanders who were present during the early stages of the fire had not received sufficient training to enable them to understand the nature of the fire that confronted them and how it was likely to develop. We do not think that the deficiencies in the system for commissioning training or the arrangements for delivering training at station level that we have identified were responsible for that shortcoming, although we cannot be confident that, if there had been sufficient understanding of the need for training in the risks of cladding fires in high-rise buildings, it would have been delivered promptly and effectively. In the next chapter we examine why the LFB failed to ensure that those who acted as incident commanders were properly trained for the task.

It became apparent during the course of the Grenfell Tower fire that few, if any, of those who were called upon to act as incident commanders in the early stages of the fire had received training in how to recognise a fire in the external wall of a high-rise residential building or to understand its likely consequences. Nor had they received any training in the principles of evacuation from high-rise residential buildings when a “stay put” strategy was no longer tenable, in how to decide whether evacuation was necessary or in how to carry it out safely and efficiently.[255] It was therefore necessary for us to examine the way in which the LFB trained those who might be expected to assume the responsibility of incident commander and in doing so we must assess its response to the recommendations on incident command made by the coroner in March 2013, following the Lakanal House inquests.

There appears to be little doubt that before the Lakanal House fire in July 2009 only a small number of officers in the LFB were aware of the dangers posed by combustible materials when used in external walls of buildings or could recognise and understand the significance of a fire of the kind that broke out in Grenfell Tower in June 2017. Those who could and did were almost entirely confined to the Fire Safety department and did not include any of those who could be expected to act as incident commanders.

The Lakanal House fire should have changed that for ever, because operational firefighters at many levels witnessed at first hand the effects of fire spreading across an external wall as a result of the presence of combustible panels. They also witnessed the extensive loss of compartmentation caused in part by the spread of fire both externally and internally, the latter as a result of the use of unsuitable materials in the refurbishment of the interior, in particular some of the corridors. That should have been enough to prompt the LFB to take urgent steps to ensure that in future incident commanders were able to recognise a rapid loss of compartmentation and the spread of fire on the exterior of a building, if it occurred, and knew how to respond, almost certainly by evacuating the whole or part of the building. However, the need for such training should have been put beyond doubt by the coroner’s rule 43 letter, written over three years after the fire.

In her rule 43 letter to the LFB the coroner recommended that consideration be given to the training of incident commanders to enhance their performance in a number of respects, including their ability to understand and react quickly to changing circumstances and to anticipate that a fire might behave in a manner inconsistent with the compartmentation principle.[256]

AC Cotton, who was head of the department responsible for incident command policy and training at the time, was asked to respond to the coroner’s recommendations.[257] Her suggested response, which was ultimately adopted by the Commissioner’s Group, was that the LFB should work with Babcock to ensure that all the points raised by the coroner were covered in its current review of incident command training in the period up to 2015 and to create a case study training package which would teach the lessons to be learnt from the Lakanal House fire and other high-rise fires, such as the one at Shirley Towers. The suggestion ultimately resulted in the Lakanal House case study, to which we will refer later. However, as noted there, the case study did not provide adequate training for incident commanders facing a widespread failure of compartmentation of the kind experienced at Lakanal House, nor did it specifically address the coroner’s incident command recommendations.[258]

The LFB accordingly instructed Babcock to incorporate the coroner’s recommendations into its review of incident command training, which by then was already in progress. In addition, the LFB instructed Babcock to conduct a separate review to confirm that all the coroner’s recommendations relating to incident command were fully covered by existing training courses.[259] That review was carried out in mid-September 2013 and the results were provided to the Operational Assurance department.[260] The results of Babcock’s review were not considered by Director Reason.[261]

Babcock concluded that the existing training explicitly or implicitly covered all the areas identified by the coroner. Some were the subject of both theoretical and practical training; in other cases the extent to which the areas identified by the coroner were covered and the performance of trainees assessed depended on the exercises they undertook. Babcock recommended that the LFB revise its existing exercises in order to implement the coroner’s recommendations and identified 16 exercises which could provide starting points for new exercises which would fully implement those recommendations.[262]