September 2024

Volume 1

Part 1 – Introduction

Part 2 – The path to disaster

HC 19–I

Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 26 of the Inquiries Act 2005

Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 4 September 2024

HC 19–I

This report contains content which some may find distressing.

© Crown copyright 2024

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3.

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents.

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected].

ISBN 978-1-5286-5080-9

(Volume 1 of 7)

E03165832 09/2024

In his introduction to his Phase 1 Report published on 30 October 2019 the chairman described the circumstances which led to the setting up of the public inquiry into the fire at Grenfell Tower on 14 June 2017. He also described the way in which the Inquiry had been organised and how it had gone about carrying out its task. Anyone who is not already familiar with those matters should refer to paragraphs 1.1 – 1.25 of that report. This second phase of the Inquiry builds on the findings made by the chairman in Phase 1 and is a direct continuation of that work. In those circumstances we do not think that it is necessary to repeat what is said in the introduction to the Phase 1 Report, but there have been some developments since it was published to which we should draw attention before turning to the substance of our report.

In Phase 1 the chairman set out to examine in detail the course of events on the night of 14 June 2017 with a view to identifying with as much confidence as possible what had taken place during the period between the outbreak of fire in the kitchen of Flat 16 at 00.54 and the escape of the last survivor at 08.07 that morning. The purpose of doing so was twofold: to enable those who had been directly involved in the fire, both residents and fire fighters, to give their accounts of the events of that night at the earliest opportunity and to find out as far as possible exactly what had happened during the early hours of 14 June 2017 before seeking to establish exactly what had gone wrong and why.

In Phase 2 we have set out to answer the question that has been at the forefront of many people’s minds: how was it possible in 21st century London for a reinforced concrete building, itself structurally impervious to fire, to be turned into a death trap that would enable fire to sweep through it in an uncontrollable way in a matter of a few hours despite what were thought to be effective regulations designed to prevent just such an event? There is no simple answer to that question, but in this report we identify the many failings of a wide range of institutions, entities and individuals over many years that together brought about that situation.

Following the publication of the Phase 1 report, the Prime Minister appointed Ms Thouria Istephan and Ms Benita Mehra as additional members of the Inquiry panel. In October 2019 Ms Redfearn resigned as an assessor and in February 2021 Mr John Mothersole, a former chief executive of Sheffield City Council, was appointed an assessor in her place, joining Mr Joe Montgomery and Professor David Nethercot, both of whom have continued to assist us generously with their time and advice. Needless to say, however, we remain entirely responsible for the conclusions in this report.

In January 2020 Ms Mehra resigned from the Panel. Mr Ali Akbor OBE was appointed in her place in October 2020.

In June 2022 Mr Mark Fisher resigned as Secretary to the Inquiry on his appointment as Chief Executive of the NHS Greater Manchester Integrated Care Board and was replaced by Ms Nicole Kett later that month. Her death in August 2022 after a short illness caused profound shock and sadness. In October 2022 Mr Matt Lewsey was appointed as Secretary in her place.

The procedure adopted in this Phase of the Inquiry has been the same as that in Phase 1. In particular, we have continued to ensure that our investigations have been as detailed and thorough as the extensive material that we have been able to gather has allowed. The chairman decided at an early stage that this phase could conveniently be divided into a number of separate modules, each reflecting an aspect of the background to the fire. That enabled the evidence to be adduced in an orderly way and minimised the need to call witnesses more than once. In most cases it also allowed expert evidence to be heard immediately after the factual evidence to which it related.

The Inquiry sat to hear evidence and opening and closing statements for Phase 2 for a total of 312 days. The hearings for Phase 2 began on 27 January 2020 but were interrupted almost immediately for a period of about five weeks at the instigation of certain core participants while an undertaking was obtained from the Attorney General to protect witnesses from the risk of having their evidence used against them in criminal proceedings.[1] Hearings began again in earnest on 2 March 2020 but had to be suspended on 16 March 2020 as a result of the restrictions imposed in response to the Covid 19 pandemic. Hearings resumed on 6 July 2020 and continued until 9 December 2020. During that period access to the hearing room was limited to those whose presence was essential, but the proceedings continued to be streamed and could be viewed by anyone interested in doing so.

Between 9 December 2020 and 8 February 2021 the proceedings were interrupted again by restrictions imposed in response to the pandemic, but between 8 February 2021 and 25 March 2021 our increasing familiarity with remote conferencing facilities and the outstanding assistance of our technical support teams at RTS Communications and Opus 2 International made it possible for us to continue hearings while observing the requirements of lockdown. On 19 April 2021 we were able to resume hearings at 13 Bishop’s Bridge Road, albeit still with restricted access. Unrestricted public access to the hearing room resumed in September 2021 and continued until November 2022.

As before, all witness statements and documents put in evidence during the course of the hearings have been published on the Inquiry’s website and the proceedings have been streamed live on the internet. In addition, arrangements were made for the proceedings to be video-recorded and transcribed and for access to both the video-recording and the transcript to be available through the Inquiry’s website.

In his introduction to the Phase 1 report the chairman explained the effect of rule 13 of the Inquiry Rules and the approach that he had decided to take to sending warning letters to those who might be subject to criticism.[2] In this phase we decided that we should take the same approach, but that inevitably presented us with a considerable challenge, given the number of people who were likely to face criticism of one kind or another. Between June 2023 and April 2024 the Inquiry’s solicitors wrote to 247 individuals and organisations informing them of the criticisms that we were minded to make of them and providing them with the relevant chapters of the draft report identifying the evidence on which those potential criticisms were based.

Between July 2023 and May 2024 the Inquiry received responses from the vast majority of those to whom warning letters had been sent, but the process as a whole took much longer than had been expected because in some cases the amount of material that a recipient had to consider was substantial. All the responses were carefully considered and in some cases we modified our provisional conclusions in the light of them. As in Phase 1, however, for the reasons explained by the chairman in the Phase 1 Report we did not take into account fresh evidence or new arguments that could have been, but had not been, put forward during the hearings.[3]

In pursuing our investigations we have had the benefit of receiving the expert advice and assistance of a number of leading practitioners in a wide range of disciplines, all of whom provided us with written reports and subsequently gave evidence to the Inquiry at public hearings. We are most grateful to all of them for the enormous amount of time they devoted to our work and the enthusiasm which they brought to it. In most cases their opinions were not seriously challenged, but to the extent that they were, we have set out the points made in opposition to their evidence in the body of our report and have given reasons for our conclusions. Except in those cases, however, we consider that the weight of their expertise and the absence of any real challenge to their evidence justifies us in accepting their opinions unless we have some good reason not to do so. Where we have relied on their evidence we have identified in footnotes the relevant passages in their reports or oral evidence without referring to them in the body of the text.

Section 2(1) of the Inquiries Act 2005 expressly prohibits us from ruling on questions of legal liability, civil or criminal. That is a matter for the courts. However, section 2(2) expressly provides that we are not to be inhibited in the discharge of our functions by any likelihood of liability being inferred from any facts we find or recommendations we make.

When dealing with an area of activity, such as the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower, which involved a large number of organisations bound together by a web of contracts and subject to legislation in the form of the Building Regulations, it is impossible to describe the relationships between them and their individual responsibilities without referring to those contracts and the relevant regulations. We have taken the view, therefore, that to refer to them merely for what they state does not amount to determining liability and we have not expressed a view about any disputes that may exist between the parties to the refurbishment or others about their respective obligations. The contracts and the regulations say what they say and establish certain relationships; we have simply treated them as part of the context in which our findings are to be read.

It is not possible to identify any single cause of the tragedy; many different acts and omissions combined to bring about the Grenfell Tower fire, although some were more significant than others. With some exceptions we have not attempted to apportion blame. We have in general asked ourselves whether a particular act or omission contributed in some way to the fire and, if so, to what extent.

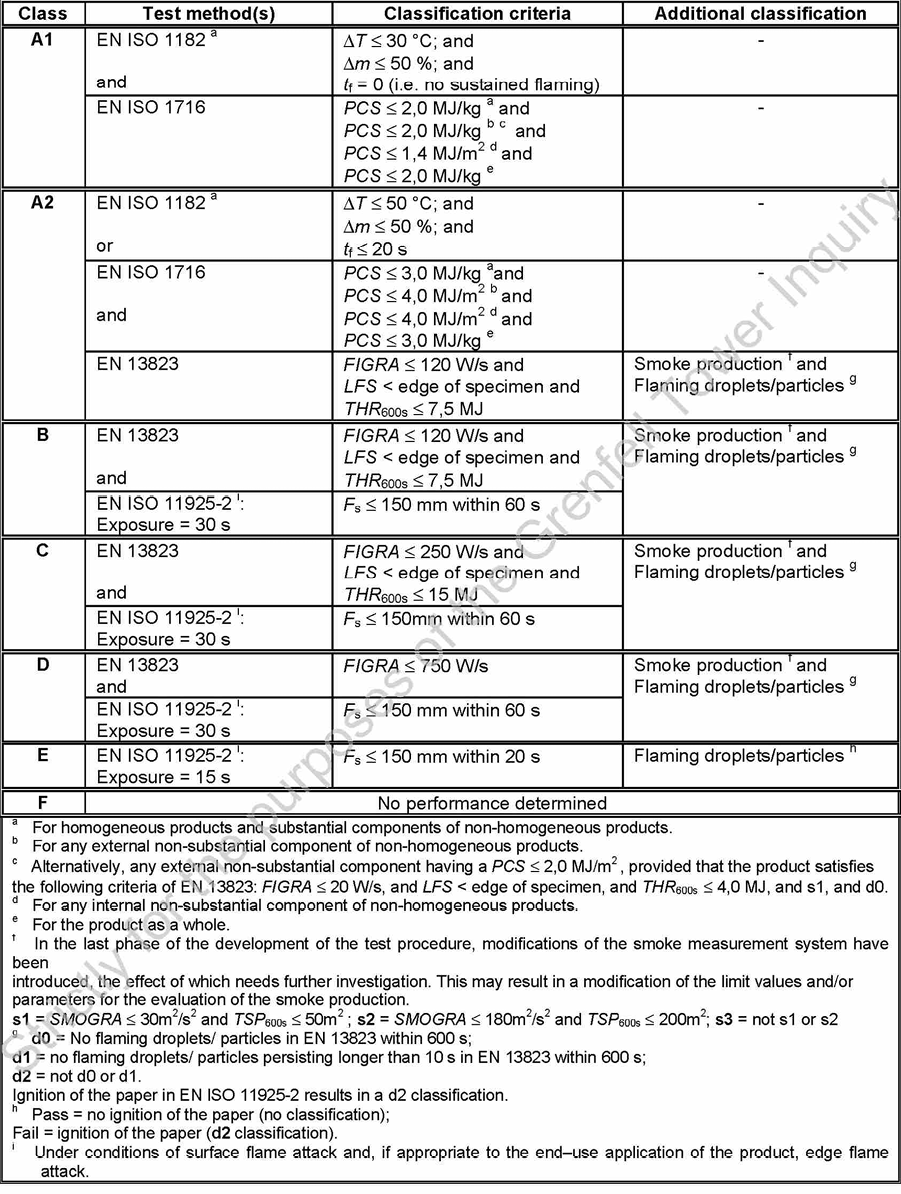

In response to the evidence that emerged during the Inquiry, all of which was published contemporaneously in one form or another, the government has already taken steps to overhaul the regulation of various aspects of the construction industry. In particular, it has prohibited the use of metal composite materials with unmodified polyethylene cores on external walls of buildings of any height, it has prohibited the use of materials that are not classed A2 (s1, d0) or better in the external walls of buildings over 18 metres in height, it has introduced new requirements for obtaining building control approval in relation to the construction and refurbishment of higher-risk buildings and has reformed the arrangements for the exercise of building control functions generally. The creation of an Office for Product Safety and Standards and the appointment of a National Regulator for Construction Products has also been put in hand and measures have been taken to improve the competence of those engaged in the design and construction of buildings generally. To that extent, it has already taken steps to cure many of the more glaring defects in the system we have identified and the scope for making recommendations is correspondingly reduced. Nonetheless, we think there are some important areas in which improvements need to be made and others in which the action taken by the government does not go far enough. In those cases we have made recommendations for change that in our view would make a significant difference to ensuring that fires of the kind that destroyed Grenfell Tower and took the lives of many of its occupants never occur again.

From the earliest days of the Inquiry there have been those who have asserted that discrimination on the grounds of race or social background played a significant part in the tragedy that befell Grenfell Tower on 14 June 2017. Originally that was reflected in calls for the Inquiry to examine social housing policy generally as well as the way in which flats in Grenfell Tower had been allocated. Those calls reflected a widely held belief that people of minority ethnic and socially disadvantaged backgrounds were routinely the subject of active discrimination that took the form of making available to them low quality or unsafe housing. A large proportion of the residents of Grenfell Tower at the time of the fire were from ethnic minorities and many were socially disadvantaged. The implication was that they had been allocated flats in what was known to be an unsafe building as a result of racial and social discrimination.

It may well be that the Grenfell Tower fire has raised questions about social housing policy, whether in RBKC or more generally, that deserve examination, though whether a public inquiry conducted under the Inquiries Act 2005 is the most suitable method of doing so may be open to debate. To have acceded to the calls for us to undertake that task, however, would have extended the scope of the Inquiry (and the time taken to produce a report) very significantly, since, even if limited to the allocation of social housing by RBKC, it would have required an examination of the council’s housing records over a period of some years. Any examination of social housing policy more widely would have extended that task enormously. As a result, the Prime Minister decided not to include those matters in the Inquiry’s Terms of Reference.

Nonetheless, at various stages during the Inquiry we have been urged to investigate what is alleged to have been a culture of racial and social discrimination in the institutions involved in one way or another in the refurbishment, particularly RBKC and the TMO. The desire to investigate and expose discrimination of that kind flowed from the undeniable fact that a significantly disproportionate number of those who died in the fire and of those who survived the fire but whose homes were destroyed were from ethnic minorities or socially disadvantaged.

For the reasons we have explained, the existence of racial or social discrimination in the allocation of social housing falls outside our terms of reference, but any factors that affected the decisions that led to the creation of an unsafe building are within our scope and we have done our best to investigate them thoroughly. Our response to those who wanted us to investigate racial and social discrimination has always been that we would look out for it and that if we came across any evidence that racial or social prejudice might have affected any of the decisions that led, directly or indirectly, to the disaster, we would examine it thoroughly and publish our findings, as befits an inquiry seeking to uncover the truth.

We should say at once that we have seen some evidence of racial discrimination in the way in which some of those who survived the fire were treated in the days immediately following it at a time when they were at their most vulnerable and we have described what happened in Part 10 of this report. We have also seen evidence that the TMO failed over the course of years to treat residents of the tower and the Lancaster West Estate more generally with the courtesy and respect due to them. That is described in Parts 4 and 5. However, we have seen no evidence that any of the decisions that resulted in the creation of a dangerous building or the calamitous spread of fire were affected by racial or social prejudice and none of those representing the bereaved, survivors or residents has drawn any such evidence to our attention, although they have had access to all the material before us.

How Grenfell Tower came to be home to a disproportionately large number of socially disadvantaged people, many from ethnic minority backgrounds, is a question that lies outside our terms of reference. It must be remembered, however, that almost without exception they had been living there, in some cases for many years, before the refurbishment was ever contemplated. Many residents told us how much they liked living there. The tower was a concrete structure and before the refurbishment was largely impervious to fire. At the time most residents were allocated their flats it was perfectly safe and we have seen nothing to suggest that following the refurbishment anyone in the RBKC housing department thought it had ceased to be so. There was no question, therefore, of allocating homes to those of non-white ethnicity in a building known to be dangerous.

In the course of the Inquiry we have examined a very large number of documents relating to the refurbishment and many hours of testimony from those involved in designing, planning, executing and approving the work. In this report we have described in some detail the course of events that led to the disaster. We have identified many errors, due in the most part to incompetence, carelessness and a failure to take responsibility for important aspects of the work that affected fire safety. In a few cases, principally involving the manufacturers of building products, we have identified dishonesty. However, we have seen no evidence that any decisions directly affecting the design or execution of the refurbishment were affected by racial or social prejudice. Although the TMO was anxious to keep the cost of the refurbishment down, and although some of the decisions taken to achieve that end were ultimately responsible for the tragedy, we saw no evidence that any of those responsible for them was aware of their potential consequences.

Given the repeated urging by some of those representing the bereaved, survivors and residents to consider whether the race or social background of those who lived in the tower played a part in bringing about the disaster and the implicit assertion that it did, we think it right to make it clear that our investigations have not brought to light any evidence to support that conclusion.

We are only too well aware that our investigations into the fire and the production of our report have taken longer than many would have wished. However, as our work has gone on it has become increasingly apparent that the disaster was the result of shortcomings in the construction industry that were far more extensive than had previously been envisaged. As the scale of the problems became ever clearer it seemed to us that those most directly affected by the fire deserved to be given a detailed and thorough description of the circumstances that led to the fire so that they could understand how it had come about and where responsibility for it lay. We hope that they and others who read our report will be satisfied that our investigations have been as detailed and thorough as they would have wished.

An inquiry of this magnitude involves an enormous amount of work and could not be conducted without a large and well-organised team of lawyers, administrators and technical professionals. We are fortunate to have had the support throughout the duration of the Inquiry of some of the most skilled, loyal and dedicated people one could hope to find, many of whom have been working for the Inquiry since it was set up in June 2017. Some have played a very public role, while others have remained entirely in the background, but they have all played an essential part in enabling us to discharge our terms of reference. A list of those who have worked with us on our investigations can be found in Appendix C. We cannot speak too highly of their professionalism and dedication.

This chapter contains an overview of the contents of our report. Our terms of reference were broad and we have followed many lines of inquiry, sometimes with unexpected results. The report is therefore inevitably lengthy and detailed. It is not possible to summarise the whole of its contents in a few pages and we have not tried to do so. The purpose of this chapter is to describe in broad terms the contents of the report and the main conclusions we have reached about the events that culminated in the tragedy at Grenfell Tower. We hope that it will assist readers in understanding the scope of the report and directing their attention to the parts of greatest interest to them. However, there is no substitute for reading the report itself.

For ease of reference we have referred to the contents of the report under headings that correspond to those of its various Parts.

In this Part of the report we describe the course of events leading up to the fire, beginning with the regulatory regime and its development in relation to the external walls of high-rise buildings. We describe the part played by the government in the form of the then Department for Communities and Local Government in the development of the statutory guidance and the investigation into the fire at Lakanal House, Southwark in 2009. We also describe the parts played by other influential bodies in creating the circumstances in which refurbishment of Grenfell Tower took place.

We conclude that the fire at Grenfell Tower was the culmination of decades of failure by central government and other bodies in positions of responsibility in the construction industry to look carefully into the danger of incorporating combustible materials into the external walls of high-rise residential buildings and to act on the information available to them.

In the years between the fire at Knowsley Heights in 1991 and the fire at Grenfell Tower in 2017 there were many opportunities for the government to identify the risks posed by the use of combustible cladding panels and insulation, particularly to high-rise buildings, and to take action in relation to them. Indeed, by 2016 the department was well aware of those risks, but failed to act on what it knew. In particular, it failed to heed the warning of the Environment and Transport Select Committee in December 1999 that it should not take a serious fire in which people were killed before steps were taken to minimise the risks posed by some external cladding systems. It also failed to implement or keep under review the committee’s recommendation that the large-scale test that had recently been developed should be substituted in Approved Document B for previous requirements relating to the fire safety of external cladding systems (thereby abandoning Class 0).

The department also failed to pay due regard to the striking results of a large-scale test in 2001 involving aluminium composite panels with unmodified polyethylene cores, which burned violently, or to take any steps either to ascertain the extent to which panels of that kind were in use or to warn the construction industry about the risks they posed. It failed even to publish the results of the test.

On many subsequent occasions the department was made aware that national Class 0 was an inappropriate standard by which to determine the suitability of external wall panels but allowed it to remain as part of the statutory guidance until after the Grenfell Tower fire. It could and should have been removed years earlier.

The review of Approved Document B carried out by the department between 2005 and 2006 provided an opportunity to clarify the guidance on compliance with functional requirement B4(1), but the language used was vague and ill-considered words were added at a late stage in the process without proper consultation.

Between 2012 and 2017 the department received numerous warnings about the risks involved in using polymeric insulation and aluminium composite panels with unmodified polyethylene cores. It also became aware of several major cladding fires abroad involving products of those kinds. By 2013 at the latest, it knew that Approved Document B was unclear and not properly understood by a significant proportion of those working in the construction industry and by February 2016 it had become aware that some in the industry were worried that combustible insulation and aluminium composite material (ACM) panels with unmodified polyethylene cores were routinely being used on high-rise buildings in breach of functional requirement B4. However, despite what it knew, and the warnings it received from some quarters, the department failed to amend or clarify the guidance in Approved Document B on the construction of external walls.

The department itself was poorly run, in as much as the official with day-to-day responsibility for the Building Regulations and Approved Document B was allowed too much freedom of action without adequate oversight. He failed to bring to the attention of more senior officials the serious risks of which he had become aware, and they in turn failed to supervise him properly or to satisfy themselves that his response to matters affecting the safety of people’s lives was appropriate. It was a serious failure to allow such an important area of activity to remain in the hands of one relatively junior official.

The Building Research Establishment (originally known as the Fire Research Station) had been established in 1921 as a government body to carry out research into and testing of construction methods and products. After it was privatised in 1997 the department limited the scope of the advice it was asked to provide on fire safety matters. As a result, the department deprived itself of the full benefit of BRE’s advice and experience. On occasions it deliberately curtailed investigations before any proper conclusion had been reached.

The department displayed a complacent and at times defensive attitude to matters affecting fire safety. Following the fire at Lakanal House the coroner recommended that Approved Document B be reviewed, but her recommendations were not treated with any sense of urgency and officials did not explain clearly to the Secretary of State what steps were required to comply with them. Similarly, legitimate concerns about the fire risks of cladding raised by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Fire Safety were repeatedly met with a defensive and dismissive attitude by officials and some ministers.

In the years that followed the Lakanal House fire the government’s deregulatory agenda, enthusiastically supported by some junior ministers and the Secretary of State, dominated the department’s thinking to such an extent that even matters affecting the safety of life were ignored, delayed or disregarded.

During that period the government determinedly resisted calls from across the fire sector to regulate fire risk assessors and to amend the Fire Safety Order to make it clear that it applied to the exterior walls of buildings containing more than one set of domestic premises. Although it commissioned a review of the advice in the Local Government Association Guide Fire safety in purpose-built blocks of flats relating to the evacuation of vulnerable people, it failed to consult those who represented their interests.

BRE held a trusted position within the construction industry and was recognised both nationally and internationally as a leader in fire safety. However, from 1991 much of the work it carried out in relation to testing the fire safety of external walls was marred by unprofessional conduct, inadequate practices, a lack of effective oversight, poor reporting and a lack of scientific rigour.

Although BRE recognised from as early as 1991, following the fire at Knowsley Heights, that small-scale testing of the kind that provided the basis for national Class 0 did not enable a proper assessment to be made of the way in which an external wall system would react to fire, it did not draw that to the government’s attention, formally or informally. Similarly, following its large-scale test of a system incorporating aluminium composite panels with unmodified polyethylene cores in 2001, BRE failed to draw the department’s attention in clear terms to the way in which the material had behaved and the dangers it presented.

BRE’s reports into the major fires at Knowsley Heights (1991), Garnock Court (1999) and The Edge (2005) were far from comprehensive and in each case failed to identify or assess important contributory factors. The reports of fires it provided to the department were characterised by superficiality and a lack of analysis, with the result that they gave the department the false impression that the regulations and guidance were working effectively.

There were weaknesses in the way BRE carried out tests in accordance with BS 8414 and in its record-keeping, which exposed it to the risk of manipulation by unscrupulous product manufacturers, as happened in the case of the second test carried out for Celotex, the manufacturer of the insulation specified for use on Grenfell Tower. Senior BRE staff gave advice to customers such as Kingspan and Celotex on the best way to satisfy the criteria for a system to be considered safe, thereby compromising its integrity and independence. In some cases we saw evidence of a desire to accommodate existing customers and to retain its status within the industry at the expense of maintaining the rigour of its processes and considerations of public safety. The unprofessional behaviour of some of BRE’s staff was in part the result of a failure to provide them with adequate training in their responsibilities.

One very significant reason why Grenfell Tower came to be clad in combustible materials was systematic dishonesty on the part of those who made and sold the rainscreen cladding panels and insulation products. They engaged in deliberate and sustained strategies to manipulate the testing processes, misrepresent test data and mislead the market. In the case of the principal insulation product used on Grenfell Tower, Celotex RS5000, the Building Research Establishment (BRE) was complicit in that strategy.

Those strategies succeeded partly because the certification bodies that provided assurance to the market of the quality and characteristics of the products, the British Board of Agrément (BBA) and Local Authority Building Control (LABC), failed to ensure that the statements in their product certificates were accurate and based on test evidence. UKAS, the body charged with oversight of the certification bodies, failed to apply proper standards of monitoring and supervision.

Arconic Architectural Products manufactured and sold the Reynobond 55 PE rainscreen panels used in the external wall of Grenfell Tower. They were an ACM product made of two thin sheets of aluminium with a polyethylene core to provide stiffening. The material was manufactured and sold in flat sheets designed to be cut to size and attached to a metal sub-frame, either as flat panels by rivets or as three-dimensional structures, known as cassettes, by slots, making use of the force of gravity. Polyethylene burns fiercely and when used in cassette form Reynobond 55 PE was extremely dangerous.[4] From 2005 until after the Grenfell Tower fire Arconic deliberately concealed from the market the true extent of the danger of using Reynobond 55 PE in cassette form, particularly on high-rise buildings.[5]

The product in its riveted form had been classed under the European classification system B-s2, d0, but from early 2005 Arconic had been in possession of test data showing that in its cassette form the product reacted to fire in a very dangerous way and could not be classified in accordance with European standards. Nonetheless, Arconic persisted in telling the market that the panels had been classed B-s2, d0 without drawing any distinction between the cassette and riveted forms.

By late 2007 Arconic had become aware that there was serious concern in the construction industry about the safety of ACM panels and had itself recognised the danger they posed. By the summer of 2011 it was well aware that Reynobond 55 PE in cassette form performed much worse in a fire and was considerably more dangerous than in riveted form. Nonetheless, it was determined to exploit what it saw as weak regulatory regimes in certain countries (including the UK) to sell Reynobond 55 PE in cassette form, including for use on residential buildings.

Despite the knowledge gained from cladding fires in Dubai in 2012 and 2013, Arconic did not consider withdrawing Reynobond 55 PE in favour of the fire-resistant version then available. Instead, it allowed customers in the UK to continue buying the unmodified product, giving them to understand that it would tell them if it was unsuitable for the use to which they intended to put it, although without any intention of doing so.

Following further testing in 2013, Arconic decided that Reynobond 55 PE would be certified as Class E only, whether used in riveted or cassette form. However, it did not pass that information to its customers in the UK or to the BBA. That was not an oversight. It reflected a deliberate strategy to continue selling Reynobond 55 PE in the UK based on a statement about its fire performance that it knew to be false.

In December 2014 the French testing house Centre Scientifique et Technique du Bâtiment (CSTB) classified the panels in riveted form as Class C and the panels in cassette form as Class E. However, Arconic failed to inform the BBA of those revised classifications.

Although Reynobond 55 PE required some degree of fabrication and could not be used in the form in which it left the factory, Arconic persuaded the BBA to issue a certificate that drew no distinction between the different forms of fixing. It concealed important information from the BBA, in particular the test data relating to the product in cassette form, that showed that it performed much worse than in riveted form. It caused the BBA to make statements in the certificate that Arconic knew to be false and misleading.

Celotex manufactured RS5000, a combustible polyisocyanurate foam insulation. In an attempt to break into the market for insulation suitable for use on high-rise buildings, created and then dominated by Kingspan K15, Celotex embarked on a dishonest scheme to mislead its customers and the wider market.[6]

With the complicity of BRE, in May 2014 Celotex tested in accordance with BS 8414 a system incorporating RS5000 that contained two sets of fire-resistant magnesium oxide boards placed in critical positions to ensure that it passed. It then obtained from BRE a test report that omitted any reference to the magnesium oxide boards, thereby rendering it materially incomplete and misleading.

Celotex then marketed RS5000 as “the first PIR board to successfully test to BS 8414”, and as “acceptable for use in buildings above 18 metres in height”. However, the test on which Celotex relied in support of that claim had been manipulated as we have described above, a fact that Celotex did not disclose in its marketing literature. Moreover, BS 8414 is a system test and does not involve the testing or classification of individual products. Celotex deliberately tucked that information away in the small print of its marketing literature.

RS5000 had previously been marketed as FR5000. From 2011 it had been sold as having Class 0 fire performance “throughout”, a claim which was false and misleading. Celotex presented RS5000 to Harley as suitable and safe for use on Grenfell Tower, although it knew that was not the case.

From 2005 until after this Inquiry had begun, Kingspan knowingly created a false market in insulation for use on buildings over 18 metres in height by claiming that K15 had been part of a system successfully tested under BS 8414 and could therefore be used in the external wall of any building over 18 metres in height regardless of its design or other components. That was a false claim, as it well knew, because BS 8414 is a method for testing complete wall systems and its results apply only to the particular system tested. As Kingspan knew, K15 could not honestly be sold as suitable for use in the external walls of buildings over 18 metres in height generally, but that is what it had succeeded in doing for many years.[7]

In marketing K15 Kingspan relied on the results of a single BS 8414-1 test performed in 2005 on a system whose components were not representative of a typical external wall and it continued to rely on that test without disclosing that it had changed the composition of the product in 2006. Tests performed in 2007 and 2008 on systems incorporating the then current form of K15 were disastrous, but Kingspan did not withdraw the product from the market, despite its own concerns about its fire performance.

Kingspan concealed from the BBA the fact that the product it was selling, to which the certificate issued in 2008 referred, differed from the product that had been incorporated into the system tested in 2005. Moreover, the BBA certificate contained three important statements about the fire performance of K15 that were untrue. It used a form of words suggested by Kingspan and drawn from its own marketing literature.

In 2009 Kingspan succeeded in obtaining from the LABC a certificate that contained false statements about K15 and supported its use generally on buildings over 18 metres in height. Kingspan relied on that certificate for many years to sell the product. It made a calculated decision to use the LABC certificate to mask, or distract from, the absence of supporting test evidence.

When the BBA certificate was re-issued in 2013, Kingspan persuaded the BBA to include a statement that K15 complied with paragraph 12.7 of Approved Document B, which wrongly implied that it was a product of limited combustibility.

When it did return to carrying out tests on systems incorporating K15, Kingspan did not use the product currently on the market but used modified or trial versions. It dishonestly relied on the results of those tests to support the sale of K15 for use on buildings over 18 metres in height and continued to do so until October 2020.

Kingspan’s claim that K15 met the requirements for Class 0 was based on a test of the foil facer alone and was disingenuous.

Kingspan cynically exploited the industry’s lack of detailed knowledge about BS 8414 and BR 135 and relied on the fact that an unsuspecting market was very likely to rely on its own claims about the product, not least because the BBA certificate directed the buyer to consult Kingspan in relation to its use on buildings over 18 metres in height.

Siderise manufactured the Lamatherm cavity barriers used in the refurbishment. Although there is no evidence of any dishonesty on its part, some aspects of its marketing materials gave cause for concern. It also supplied cavity barriers for use in voids larger than those for which they had been tested.

The British Board of Agrément (BBA) is a commercial organisation that certifies the compliance of products with the requirements of legislation. It issued certificates of compliance in respect of one of the insulation products used on Grenfell Tower, Kingspan K15, and the Reynobond 55 PE panels used as the rainscreen. Its certificates were accepted in the industry largely without question but its procedures were neither wholly independent nor rigorous and were not always rigorously applied.

The dishonest strategies of Arconic and Kingspan succeeded in a large measure due to the incompetence of the BBA, its failure to adhere robustly to the system of checks it had put in place, and an ingrained willingness to accommodate customers instead of insisting on high standards and adherence to a contract that was intended to maintain them. As a result of systemic shortcomings and inadequate levels of competence and technical expertise among its staff, its scrutiny of the fire performance of K15 and Reynobond 55 PE was seriously deficient and the certificates it produced for those products were misleading.

The underlying problem was that the BBA failed to manage the conflict between the need to act as a commercial organisation in order to attract and retain customers and the need to exercise a high degree of rigour and independence in its investigations in order to satisfy those who might consider relying on its certificates. It accepted for inclusion in certificates forms of wording proposed by manufacturers that were wrong and misleading. Its lack of robust processes and reluctance to enforce the terms of its contracts enabled it to become the victim of dishonest behaviour on the part of unscrupulous manufacturers.

So far as Reynobond 55 PE was concerned, the certificate issued by the BBA in 2008 contained false statements, including that the product “may be regarded as having a Class 0 surface”. The BBA accepted the results of tests carried out on a different product. It failed to take advice from BRE when drafting the certificate. It completed and approved periodic reviews and re-issued the certificate without having received any new information, despite having asked Arconic repeatedly to provide it. It failed to suspend or withdraw the certificate in response to Arconic’s failure to co-operate.

Until December 2013 the BBA effectively allowed the contents of the certificates relating to Kingspan K15 to be dictated by Kingspan itself, including the requirement to seek advice from Kingspan in relation to the use of the product on buildings over 18 metres in height. The BBA did not assess any aspect of the product’s manufacture, testing or fire performance before it issued the certificate. It did not obtain any test data relating to K15 before it issued a certificate containing a statement that the product had been classified as national Class 0, since none existed. It ought to have known that the statement in the revised certificate issued in July 2013 implying that K15 was a material of limited combustibility was false because K15 was a phenolic foam product.

Local Authority Building Control (LABC) is a body formed by local authority building control departments in 2005 to provide support with training and technical matters and to provide centralised marketing and business development services for members. Following an initial assessment by a local authority building control surveyor and a second stage review by a group of experts, it issued certificates verifying the compliance of construction products and systems with the Building Regulations and Approved Documents.

The LABC must take its share of the blame for the acceptance by the market of Celotex RS5000 and Kingspan K15 for use on buildings over 18 metres in height. There was a complete failure on the part of the LABC over a number of years to take basic steps to ensure that the certificates it issued in respect of them were technically accurate.

The LABC was vulnerable to manipulation because its processes were not implemented rigorously enough. The task of producing an initial assessment should not have been given to building control officers, who did not have the degree of knowledge and experience necessary to make an informed assessment of the product in question, and those who carried out the second stage review were not always competent to do so and in some cases did not take the necessary degree of care.

Over a period of some years the LABC’s certificates relating to Kingspan K15 and Celotex RS5000 contained misleading statements about their fire performance and about the suitability of both products for use in the external walls of buildings over 18 metres in height. Despite warnings from various quarters, the LABC failed to scrutinise properly the claims made for the products by the manufacturers and instead adopted uncritically the language they suggested. In short, it was willing to accommodate the customer at the expense of those who relied on the certificates. As a result, the LABC was also the victim of dishonest behaviour on the part of unscrupulous manufacturers.

The National House Building Council (NHBC) employed a large number of Approved Inspectors through whom it provided building control services to a large part of the housing construction industry. It also wielded considerable influence on the industry through its membership of the Building Control Alliance, a body established in 2008 to promote the role of building control bodies, and its publication of guidance notes. However, it failed to ensure that its building control function remained essentially regulatory and free of commercial pressures. It was unwilling to upset its own customers and the wider construction industry by revealing the scale of the use of combustible insulation in the external walls of high-rise buildings, contrary to the statutory guidance. We have concluded that the conflict between the regulatory function of building control and the pressures of commercial interests prevents a system of that kind from effectively serving the public interest.

BRE played an important part in enabling Celotex and Kingspan to market their products for use in the external walls of buildings over 18 metres in height. BRE’s systems were not robust enough to ensure complete independence and the necessary degree of technical rigour at all times. As a result, it sacrificed rigorous application of principle to its commercial interests. From 2004 it had engaged in discussions with Kingspan about the steps it might take to ensure that a system incorporating K15 met the performance requirements, and during the test of a system incorporating K15 in March 2014 it gave advice on its performance, including how the results of the test might be interpreted. It accepted the inclusion of magnesium oxide boards in the system incorporating RS5000 tested for Celotex in May 2014.

UKAS did not always follow its own policies and its assessment processes were lacking in rigour and comprehensiveness. Even when failings were identified they were not properly explored and opportunities to improve were not always taken. The process relied too much on the candour and co-operation of the organisations being assessed and too much was left to trust. UKAS should have taken a more searching, even sceptical, attitude to the organisations it accredited. Its powers to take action were surprisingly limited, with no powers of enforcement. The most it could do in response to unsatisfactory conduct was to suspend or withdraw accreditation.

The relationship between the TMO and its residents had been a troubled one for many years before the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower. Two independent reports in 2009 had drawn attention to numerous serious flaws in that relationship. The second of those reports identified governance, customer service, staff attitudes and a poor repairs service as constant themes of the investigation. It also found that the residents’ lack of trust in the TMO lay at the heart of the problems. The reports made some 34 recommendations for change.

Despite those penetrating reports and the recommendations they contained, eight years later the TMO had shown little sign of any change and appeared to have learnt nothing about how to treat, or relate to, its residents.

We have concluded from all the evidence that from 2011 to 2017 relations between the TMO and many of the residents of Grenfell Tower were increasingly characterised by distrust, dislike, personal antagonism and anger. Some, perhaps many, occupants of the tower regarded the TMO as an uncaring and bullying overlord that belittled and marginalised them, regarded them as a nuisance, or worse, and failed to take their concerns seriously. For its part, the TMO regarded some of the residents as militant troublemakers led on by a handful of vocal activists, principally Edward Daffarn, whose style they found offensive. The result was a toxic atmosphere fuelled by mistrust on both sides.

In the end, however, responsibility for the maintenance of the relationship between the TMO and the Grenfell community fell not on the members of that community, who had a right to be treated with respect, but on the TMO as a public body exercising control over the building which contained their homes. The TMO lost sight of the fact that the residents were people who depended on it for a safe and decent home and the privacy and dignity that a home should provide. That dependence created an unequal relationship and a corresponding need for the TMO to ensure that, whatever the difficulties, the residents were treated with understanding and respect. We have concluded that the TMO failed to recognise that need and therefore failed to take the steps necessary to ensure that it was met.

However irritating and inconvenient it may at times have found the complaints and demands of some of the residents of Grenfell Tower, for the TMO to have allowed the relationship to deteriorate to such an extent reflects a serious failure on its part to observe its basic responsibilities.

RBKC and the TMO were jointly responsible for the management of fire safety at Grenfell Tower. The years between 2009 and 2017 were marked by a persistent indifference to fire safety, particularly the safety of vulnerable people. We have examined in detail a wide variety of matters that have led us to that conclusion, the most prominent of which we set out here.

RBKC was responsible for overseeing the TMO’s activities, not monitoring its operations on a day-to-day basis, but its oversight of the TMO’s performance was weak and fire safety was not subject to any key performance indicator. The absence of any independent or rigorous scrutiny by RBKC of the TMO’s performance of its health and safety obligations, and in particular its management of fire safety, was a particular weakness. RBKC took little or no account of an independent and highly critical review of fire safety carried out for the TMO in 2009. It did not even know about a further independent and highly critical report produced in 2013 because the TMO had failed to disclose it to RBKC.[8]

The TMO’s performance of its own functions and the effectiveness of RBKC’s oversight depended on full and candid reporting by the TMO’s senior management to its board. Although there was a satisfactory system for senior management to report to the board and to RBKC, it did not operate effectively because of an entrenched reluctance on the part of the TMO’s chief executive, Robert Black, to inform the board and RBKC’s scrutiny committees of matters that affected fire safety. That failure was all the more serious because there were chronic and systemic failings in the TMO’s management of fire safety of which the board should have been made aware. Robert Black consistently failed to tell either the board or RBKC of the LFB’s concerns about the TMO’s compliance with the Fire Safety Order or the steps taken to enforce it.

First, although in 2009 an independent fire safety consultant had recommended that a fire safety strategy be prepared, nothing was done until November 2013 and a strategy had still not been finally approved by the time of the Grenfell Tower fire.

Secondly, the TMO’s only fire assessor for its entire estate, Carl Stokes, was allowed to drift into that role without any formal selection or procurement process. He had misrepresented his experience and qualifications (some of which he had invented) and was ill-qualified to carry out fire risk assessments on buildings of the size and complexity of Grenfell Tower, let alone to hold the entire TMO portfolio. As a result there was a danger that fire risk assessments would not meet the required standard.

Thirdly, although Mr Stokes’ methods for carrying out fire risk assessments generally reflected the Health and Safety Executive’s five steps for managing risks, the LGA Guide and PAS 79, they suffered from serious shortcomings. He often failed to check whether the TMO had taken action in response to risks he had identified in previous assessments. Despite the concerns expressed by the LFB about his competence, the TMO continued to rely uncritically on him, a situation which made the danger more acute in the absence of any arrangements for assessing the quality of his work.

Fourthly, there was no adequate system for ensuring that defects identified in fire risk assessments were remedied effectively and in good time. The TMO developed a huge backlog of remedial work that it never managed to clear, a situation that was aggravated by the failure of its senior management to treat defects with the seriousness they deserved. Indeed, on one occasion senior management intervened to reduce the importance attached to the implementation of remedial measures. The demands of managing fire safety were viewed by the TMO as an inconvenience rather than an essential aspect of its duty to manage its property carefully.

Certain important features of the fire prevention measures at Grenfell Tower were not of an appropriate standard. For example, the new front doors installed by the TMO in 2011 and 2012 did not meet the fire resistance standards suggested by Approved Document B because the TMO had failed to specify the correct fire safety standard when ordering them.

Inspection and maintenance regimes affecting fire prevention systems did not reflect best practice and were inconsistently followed. Many self-closing devices on the front doors of flats in Grenfell Tower failed to work effectively and some were missing entirely. The TMO did not institute an effective inspection and maintenance programme for self-closing devices on entrance doors despite an Enforcement Notice issued by the LFB in late 2015 relating to ineffective door closers in another high-rise residential building it managed, Adair Tower, and a Deficiency Notice issued in 2016 in relation to Grenfell Tower itself on the same grounds.

Although the TMO had no obligation to produce a general evacuation plan, its Emergency Plan for Grenfell Tower was out of date and incomplete and did not reflect the changes brought about by the refurbishment. The TMO was well aware of that fact following a fire at Adair Tower in October 2015, but failed to address it. The absence of fire action notices in the tower was a prominent subject of complaints by residents and led to the issue of a Deficiency Notice in November 2016.

The Grenfell Tower fire revealed the importance of ensuring that the responsible person under the Fire Safety Order collects sufficient information about any vulnerable occupants to enable PEEPs to be prepared, when appropriate, and, in the event of a fire, appropriate measures to be taken to assist their escape. The TMO did take some steps to gather information of that kind, both before and during the refurbishment, but its data systems were not properly co-ordinated. Such information as was collected was not always used to revise its records, with the result that the spreadsheet available on the night of the fire was incomplete. The TMO’s failure to collect such information amounted to a basic neglect of its obligations in relation to fire safety.

In this Part we trace the origins of the refurbishment project and its relationship to the Kensington Aldridge Academy and Leisure Centre (KALC) projects. We describe the persons and organisations principally involved in the project and the legislative background against which the refurbishment was carried out. We also identify two significant problems relating to Approved Document B that in our view call for urgent attention. The first is the assumption that compliance with functional requirements B3 and B4 will provide a high degree of compartmentation, thus rendering evacuation of the building unnecessary. The second is the tension between functional requirements of the Building Regulations and the prescriptive language of the guidance and the propensity of many in the industry to treat the guidance as definitive.

We explain how the KALC project influenced the appointment of Studio E as architect and describe the way in which the TMO manipulated the procurement process to avoid having to put the contract for architectural services out to public tender. Artelia was appointed by the TMO as a consultant, having acted as employer’s agent and quantity surveyor for the KALC project.

The initial plans for the refurbishment ran into difficulties because the estimated cost of the project produced by the principal contractor on the KALC project exceeded the budget by a significant margin. However, in about May 2013 the TMO’s former emphasis on maintaining the momentum of the project changed to one of saving cost. That led in turn to a recommendation, reluctantly supported by Artelia, that a principal contractor should be appointed through a formal procurement process. Such a process was then implemented.

Although Rydon’s tender was judged to be the most competitive, it still exceeded the TMO’s budget. As a result, although the TMO had received advice from its lawyers that it would be improper to do so, it entered into discussions with Rydon before the procurement process had been completed leading to an agreement that, if Rydon were awarded the contract, it would reduce its price to an acceptable level.

Although Studio E had wanted to use zinc rainscreen panels, cost became an increasingly important consideration for the TMO and eventually an aluminium composite material (ACM), Reynobond 55 PE, was chosen, largely on the grounds of cost. Rydon was able to offer a substantial saving through the use of ACM panels as a result of its relationship with its intended cladding sub-contractor, Harley.

The choice of combustible materials for the cladding of Grenfell Tower resulted from a series of errors caused by the incompetence of the organisations and individuals involved in the refurbishment. Studio E, Rydon and Harley all took a casual approach to contractual relations. They did not properly understand the nature and scope of the obligations they had undertaken, or, if they did, paid scant attention to them. They failed to identify their own responsibilities for important aspects of the design and in each case assumed that someone else was responsible for matters affecting fire safety. Everyone involved in the choice of the materials to be used in the external wall thought that responsibility for their suitability and safety lay with someone else.

None of those involved in the design of the external wall or the choice of materials acted in accordance with the standards of a reasonably competent person in their position. They were not familiar with or did not understand the relevant provisions of the Building Regulations, Approved Document B or industry guidance. Studio E demonstrated a cavalier attitude to the regulations affecting fire safety and Rydon and Harley relied on their previous experience rather than on any technical analysis or expertise. The risks of using combustible materials in the external walls of high-rise buildings were well known and they should have been aware of them.

RBKC building control did not properly scrutinise the design or choice of materials and failed to satisfy itself that on completion of the work the building would comply with the requirements of the Building Regulations.

Exova was instructed by Studio E on behalf of the TMO to prepare a fire safety strategy for the building in its refurbished form. A draft was prepared but never completed. In particular, it did not include an analysis of the external wall or its compliance with functional requirement B4(1) of the Building Regulations.

Although our criticisms are directed principally towards Studio E, Exova, Rydon, Harley and RBKC building control, the TMO must also bear a share of the blame for the disaster because it failed to ensure that the position of Exova was clarified after Rydon had been appointed and that the fire safety strategy was completed.

As architect Studio E was responsible for the design of the external wall and for the choice of the materials used in its construction.[9] Although the TMO as the client wanted to reduce the cost by using ACM rainscreen panels, it was the responsibility of Studio E to determine whether the use of such material would enable the building to comply with functional requirement B4(1) of the Building Regulations and advise the TMO accordingly. Its failure to recognise that ACM was dangerous and to warn the TMO against its use represented a failure to act in accordance with the standard of a reasonably competent architect. It also failed to recognise that Celotex insulation was combustible and not suitable for use on a building over 18 metres in height in accordance with the statutory guidance. Studio E therefore bears a very significant degree of responsibility for the disaster.

We have identified many other respects in which Studio E failed to meet the standards of a reasonably competent architect, of which the following are the most significant. It failed to ensure that Exova completed the fire safety strategy for the refurbished building or advise Rydon and the TMO that it should be required to do so. It failed to understand that it was responsible for design work carried out by sub-contractors and so did not check Harley’s designs to ensure that on completion the building would comply with the Building Regulations. It did not devise a proper cavity barrier strategy or check Harley’s designs for the cavity barriers and it failed to produce detailed drawings of the window reveals or to notice that the materials specified for the window infill panels were unsuitable.

Exova also bears considerable responsibility for the fact that Grenfell Tower was in a dangerous condition on completion of the refurbishment.[10] Our most serious criticism is that it failed to produce a final version of the fire safety strategy for the refurbished building and that it failed either to draw that fact to the attention of the design team or to warn it about the potential consequences. None of those responsible for drafting the fire safety strategy visited Grenfell Tower; the only site visit by a member of Exova’s staff took place at a preliminary stage. Exova’s attitude was wholly inconsistent with the careful approach to matters affecting the safety of life to be expected of a reasonably competent fire engineer.

We consider that the principal contractor, Rydon, also bears considerable responsibility for the fire.[11] It gave inadequate thought to fire safety, to which it displayed a casual attitude throughout the project and its systems for managing the design work did not ensure that its sub-contractors and consultants properly understood their different responsibilities. Rydon itself did not understand where responsibility for individual decisions lay and as a result it failed to co-ordinate the design work properly.

Rydon had an inexperienced team on the refurbishment that did not have sufficient knowledge of the Building Regulations or Approved Document B. It relied entirely on its cladding sub-contractor, Harley, to draw its attention to any errors in the design, but it did not specifically ask Harley to assess Studio E’s work. It failed to take proper steps to investigate Harley’s competence and ensure that it was competent to undertake the work and capable of providing the services required of it. It was complacent about the need for fire engineering advice and took the decision not to retain Exova without consulting the TMO, Studio E or Artelia. Its understanding of the work already carried out by Exova was superficial; as a result, it failed to realise that the fire safety strategy had not been completed.

Harley itself failed in many respects to meet the standards to be expected of a reasonably competent cladding contractor and it too bears a significant degree of responsibility for the fire.[12] It did not concern itself sufficiently with fire safety at any stage of the refurbishment and appears to have thought that there was no need for it to do so, because others involved in the project, and ultimately building control, would ensure that the design was safe. It failed to ask the kind of questions about the materials being considered that a reasonably competent cladding contractor would have asked. It was induced to buy Reynobond 55 PE panels partly by its existing relationship with Arconic and the cladding fabricator, CEP Architectural Facades, with which it was able to negotiate a favourable price. Its staff were unaware of the requirements of the Building Regulations relating to fire safety, the guidance in Approved Document B or industry guidance and did not understand the underlying testing regime.

Although Celotex RS5000 (as opposed to Celotex FR5000) had not been specified, Harley accepted it for use on the tower without enquiring in any detail whether it could be safely used and did not ask any of the other members of the design team that question before doing so. Its design for the cavity barriers was incomplete and did not comply with the guidance in Approved Document B.

RBKC’s building control department failed to perform its statutory function of ensuring that the design of the refurbishment complied with the Building Regulations.[13] It therefore bears considerable responsibility for the dangerous condition of the building immediately on completion of the work. The surveyor responsible for the refurbishment was overworked, inadequately trained and had a very limited understanding of the risks associated with the use of ACM panels. He failed to obtain full information about the construction of the external wall at the stage of the full plans application and did not ask whether Exova had provided a completed fire safety strategy. He knew that ACM was to be used as the rainscreen but paid little or no attention to the BBA certificate for Reynobond 55 PE. He failed to recognise that Celotex RS5000 insulation was not a material of limited combustibility and, if he looked at any information about it, he simply accepted the assertion that it was suitable for use on tall buildings. He failed to consider whether the external wall system proposed for Grenfell Tower was the same as that tested by Celotex and said to support the use of RS5000.

The TMO must also take a share of the blame for the disaster.[14] As the client it failed to take sufficient care in its choice of architect and paid insufficient attention to matters affecting fire safety, including the work of the fire engineer.

This short chapter describes the work carried out in 2016 and 2017 to replace one of the six gas risers in Grenfell Tower that was suffering from corrosion. There were defects in the design and execution of the work, to which we draw attention. The work had not been completed by the time of the fire, but neither the defects we have identified nor the failure to have completed the work contributed to the fire.

On the night of the fire it was not possible to find the two pipeline isolation valves designed to enable the supply of gas to the tower to be shut off quickly, almost certainly because they had been covered over in the course of landscaping work. However, that did not affect the course of events surrounding the fire because burning debris falling on the east side of the tower would have prevented access to them.

The Lakanal House fire in July 2009 should have alerted the LFB to the shortcomings in its ability to fight fires in high-rise buildings that revealed themselves once more at Grenfell Tower on the night of 14 June 2017. Those shortcomings could have been made good if the LFB had been more effectively managed and led. In particular, it should have responded more effectively to its experience at Lakanal House and made better use of the knowledge it had gained of the dangers posed by modern materials and methods of construction. Importantly, it failed to ensure that in the years immediately preceding the Grenfell Tower fire regular training of a suitable kind was provided to its control room operators on handling many fire survival guidance calls concurrently and on their duties more generally. Senior managers at the LFB failed to take steps to ensure that its arrangements for handling fire survival calls reflected national guidance.

Those failures were attributable to a chronic lack of effective management and leadership, combined with an undue emphasis on process. Senior officers were complacent about the operational efficiency of the brigade and lacked the management skills to recognise the problems or the will to correct them. Those managerial weaknesses were partly the result of an historic failure to integrate the operational departments and the departments responsible for support functions, in particular the control room. There was a tendency to treat problems of which managers became aware as undeserving of change or too difficult to resolve, even when they concerned operational or public safety.

Those failures were compounded by an entrenched but unfounded assumption that the Building Regulations were sufficient to ensure that external wall fires of the kind that were known to have occurred in other countries would not occur in this country. After the Lakanal House fire senior officers recognised that compliance with the regulations could not be guaranteed, but no one appears to have thought that firefighters needed to be trained to recognise and deal with the consequences.

The main failings on the part of the LFB that led to the shortcomings identified in the Phase 1 report included a failure to identify training needs combined with a system for commissioning new training packages that was cumbersome and slow. Incident command training was poorly devised and was not effectively delivered; inadequate provision was made for refresher training and regular assessment.

The LFB failed to ensure that the knowledge of the dangers presented by the increasing use of combustible materials, in particular the risk of external fire spread and the resulting loss of compartmentation, held by some specialist officers was shared with the wider organisation and reflected in training, operational policies and procedures. Firefighters were not given proper training or guidance on how to carry out inspections of complex buildings and there were no effective arrangements for sharing information about risks posed by particular buildings. Internal recommendations for improving the inspection of high-rise residential buildings were not implemented.

The policy on high-rise firefighting did not reflect national guidance and senior management failed to recognise that producing contingency plans for a full evacuation and training firefighters to implement them was an essential aspect of fighting fires in high-rise buildings.

One significant shortcoming was a failure to recognise the possibility that in the event of a fire in a high-rise residential building a large number of calls seeking help, both from within and outside the building, might be generated. The LFB failed to take any steps to enable it to respond effectively to that kind of demand. As a result, when faced with a large number of calls about people needing to be rescued from Grenfell Tower, both those in the control room and those responsible for handling that information at the fireground were forced to resort to various improvised methods of varying reliability to handle the large amount of information they received.

The senior officers responsible for the control room understood the need to give priority to training staff in handling fire survival guidance calls, but in the years between 2010 and 2017 no structured or regular refresher training in handling fire survival guidance calls was designed or delivered to control room staff. Such training as was provided did not reflect national guidance in some respects; nor did it respond to the experience of those control room officers who had been on duty at the time of the Lakanal House fire. The failures in the effective functioning of the control room were due in a large measure to weak management over the preceding years combined with sporadic and ineffectual oversight by senior officers.

The communication equipment in use at the time of the Grenfell Tower fire proved to function inadequately in a high-rise building constructed largely of reinforced concrete. That was a well known problem but nothing had been done to alleviate it and firefighters were not trained to recognise and respond to it. The LFB’s approach was to do its best with what it had available. As a result, it failed to make sufficient efforts to modernise its equipment, thereby significantly impairing its operational efficiency. The LFB’s policies did not contemplate a widespread loss of communications or provide guidance on how it could effectively be restored.

The detailed description of the events of 14 June 2017 contained in the Phase 1 report places us in a good position to make comprehensive findings about the circumstances in which the deceased met their deaths. Although it is for the coroner to decide whether she should adopt our findings as sufficient to enable her to discharge her responsibilities, we hope that she will be able to do so and thus spare the bereaved the distress of a further investigation.

We begin this Part with a general introduction followed by a description of the painstaking methods adopted to recover and identify the remains of the individual deceased. In that context we refer to the work of the teams of forensic archaeologists, forensic anthropologists and forensic pathologists, as well as other experts and police disaster victim identification officers and licensed search officers. We also describe in general terms the evidence given by Professor David Purser CBE BSc PhD DipRCPath, an expert on toxicology.

We devote a separate chapter of this Part to each floor on which people died. After a general description of the circumstances affecting that floor, our findings deal in turn with each of those who died on, or fell from, that floor. In the case of those who died on the stairs we have described the circumstances relating to the floor on which their flat was located. In each case we give a brief description of the deceased before describing the immediate circumstances in which he or she died.

Although the evidence was sometimes rather confused, we have been able to make findings about emergency calls made by those who were trapped, the transmission of information from the LFB control room to the incident ground and thence to the bridgehead and the deployment of firefighters in response. To the extent possible we have made what we consider to be reliable findings about the time of death in each case, although in many cases there is inevitably a large measure of uncertainty. In the light of the expert evidence we are able to make findings about the cause of death, including findings that all those whose bodies were destroyed by the fire were dead or unconscious when the fire reached them.

In the first week after the fire at Grenfell Tower the response of the government and RBKC was muddled, slow, indecisive and piecemeal. RBKC’s systems and leadership were wholly inadequate to the task of handling an incident of such magnitude and gravity, involving, as it did, mass homelessness and mass fatalities. The resilience machinery in London and within central government was not flexible enough and took too long to move into action.

Certain aspects of the response demonstrated a marked lack of respect for human decency and dignity and left many of those immediately affected feeling abandoned by authority and utterly helpless. RBKC should have done more to cater for those from diverse backgrounds, in particular those many residents of the Muslim faith who were observing Ramadan at the time. They were left feeling that the council had no regard for their cultural and religious needs. For many, their only source of support was local voluntary organisations, which moved in to help and provide for basic needs where those in authority had failed. Many who had particular religious, cultural or social needs suffered a significant degree of discrimination in ways that could and would have been prevented if the guidance had been properly followed.

The response to the disaster was inadequate principally because RBKC did not have an effective plan to deal with the displacement of a large number of people from their homes and such plan as it did have did not make effective use of the TMO. It had made no contingency arrangements for obtaining a large amount of emergency accommodation at short notice and had no arrangements for identifying those who had been forced to leave their homes or for communicating with them. Arrangements for obtaining and disseminating reliable information were also lacking.

One reason for the lack of effective plans was that RBKC had failed to train its staff adequately. They did not have a sufficient understanding of the importance of resilience or sufficient commitment to it. Exercises had not been held regularly and staff had not been required to attend the training sessions run by the London Resilience Group. Deficiencies that were well known to senior management had not been corrected.

Over a number of years, RBKC had allowed the capacity of its staff to respond to major emergencies to decline. There had been clear warnings to senior management that it did not have enough trained staff to enable it to carry out its responsibilities as a Category 1 responder and that contingency plans had not been practised enough. As a consequence, RBKC lacked the people it needed to respond to the fire effectively, both for the purposes of staffing the borough emergency communication centre and to deal with those who needed help. It was therefore ill-equipped to deal with a serious emergency. None of that was due to any lack of financial resources.

RBKC’s chief executive, Nicholas Holgate, was not capable of taking effective control of the situation and mobilising support of the right kind without delay. He had no clear plan and did not receive all the information he needed. He was not well suited to dealing with the crisis that was unfolding in front of him and lacked a strong group of officers to whom he could delegate responsibility for some aspects of the response. He was reluctant to take advice from those with greater experience and was unduly concerned for RBKC’s reputation.

RBKC had failed to integrate the TMO into its emergency planning. It should have realised that the TMO’s knowledge of its buildings and their occupants could play an important part in the response to any disaster affecting any part of its housing stock.